Bolsover Successful Healthy Places SPD 2025

3. Place Making Principles

3.1 Movement

3.1.1 A balanced approach to movement

Cars are likely to be used less often where layouts promotes healthy ways of living. New developments should be planned so as to reduce the demand for road space and provide the community with sustainable and realistic alternative transport options.

3.1.2 The movement network provides the skeletal framework around which the development can be formed. The early design choices are therefore critical to putting in place a well- reasoned and practical movement network that meets the needs of all its users. This means ensuring that one group's requirements do not dominate to the extent that they constrain or are detrimental to needs of other groups.

3.1.3 Equitable access throughout a development means providing users with a real choice of movement, so they can choose their own route and mode of transport. Short local trips provide the best opportunities for journeys on foot or bicycle (active travel) so these routes should be more direct than those for cars.

3.1.4 Provide charging points for electric bikes and vehicles. Implement low traffic neighbourhoods and allow for play streets.

3.1.5 Connected, integrated, permeable

Proposals should comprise a layout of permeable streets that connect to and integrate with the surrounding network of streets and paths.

3.1.6 Connecting developments with the surrounding streets and neighbourhoods allows them to physically integrate with and function as part of the established settlement, both socially and economically.

3.1.7 Developments with poor connections to adjoining areas and movement networks designed around the car result in insular, disconnected places that fail to integrate with the settlement and which reduce the inclination to walk, cycle or use public transport.

3.1.8 Conversely, integrated permeable movement networks are beneficial to both communities and help reduce car dependency. They encourage active travel by being easier to navigate and minimising walking distances to nearby facilities, which increases their pedestrian and cycle catchments.

Successful healthy places:

• Design for various essential users in a compatible way. Put the most vulnerable groups first: pedestrians first, followed by cyclists, horse riders and motorcyclists, before other vehicular traffic.

• Think about children, older adults and disabled people being more at risk. Give pedestrians a dense permeable network with priority at crossings.

• Encourage use of Shared Spaces. Respect the safety of people walking in these spaces.

• Provide movement networks that encourage walking and cycling and give easy access public transport.

• Locate bus stops within a reasonable walking distance (normally 400m), via safe routes and provide bus shelters to encourage their use.

• Provide for access by motor vehicles and accommodate the size and frequency of service vehicles without detracting from the quality of the environment.

Successful healthy places:

• Have internal permeability with interconnected streets that allow people to choose the most convenient and attractive direct option for their journey.

• Make connections to the adjacent street and footpath network, including safe, direct green pedestrian/cycle links.

• Design the movement network to connect easily to local destinations by following desire lines to where people want to go. Provide safe routes to school, wider pavements.

• Incorporate existing public rights of way into segregated attractive routes through the development.

3.1.9 Legibility

3.1.10 Making places legible is to make them easy to understand and navigate, so that people have a clear mental image of the place. They should include recognisable features that help give them a sense of place and make them memorable.

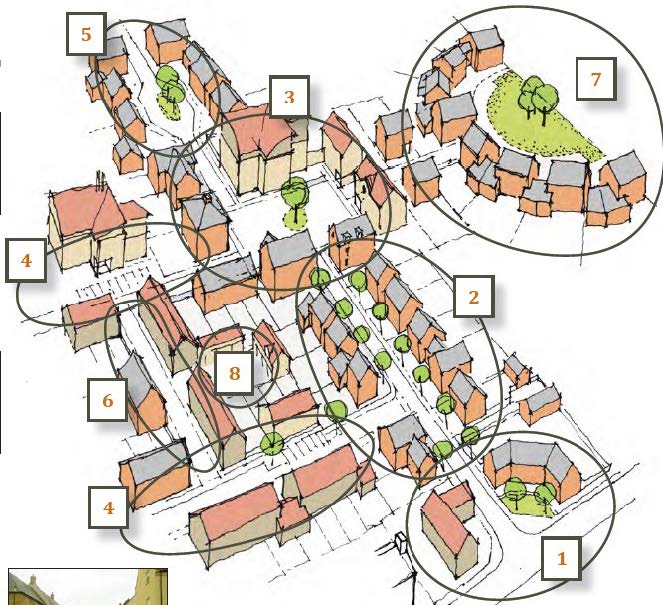

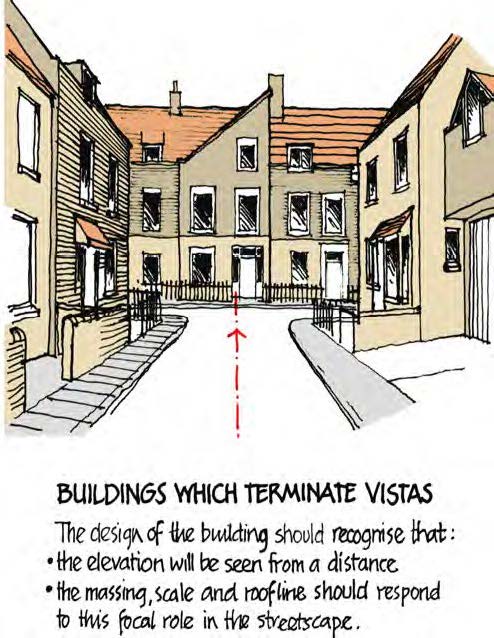

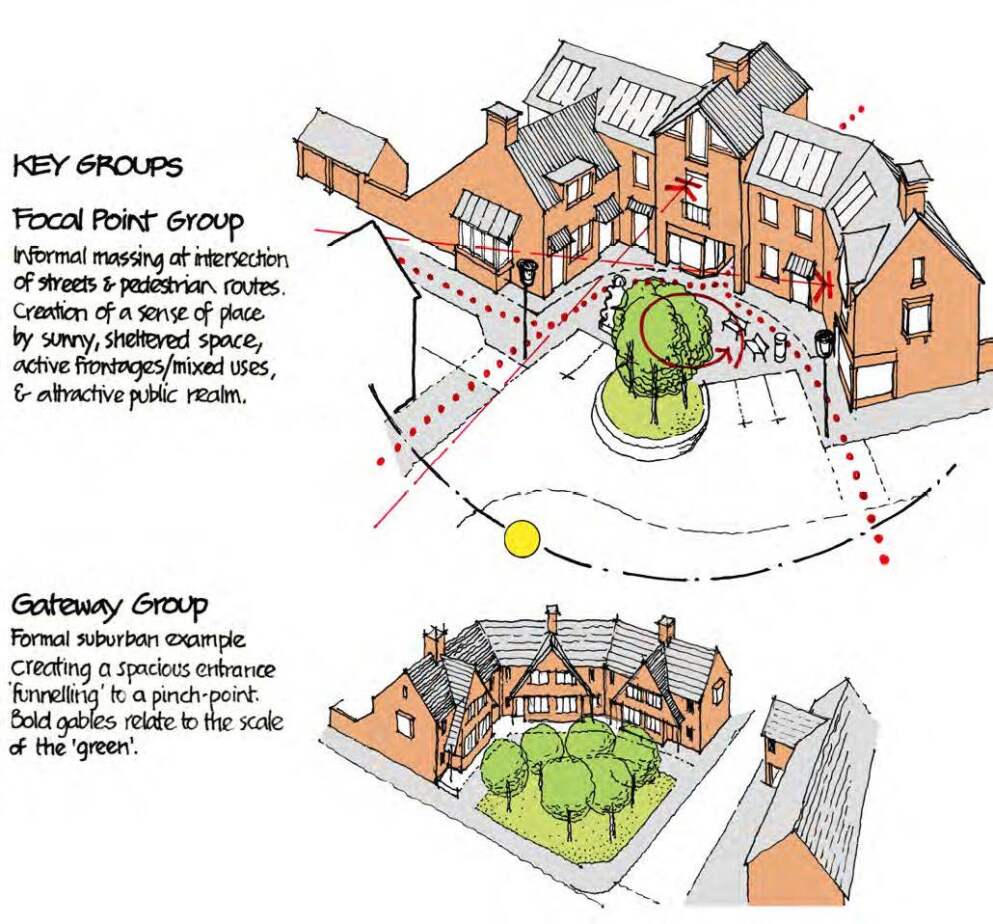

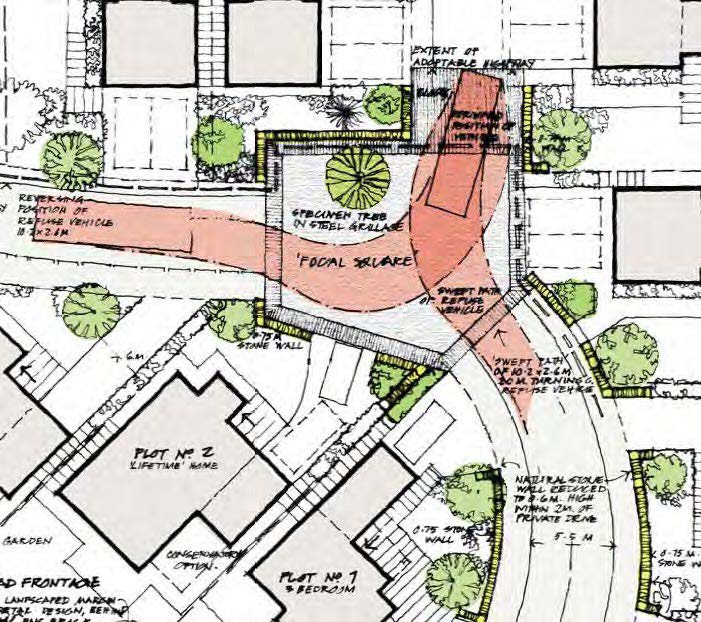

3.1.11 Memorable spaces may contain a focal point such as a piece of public art or a mature tree. Key nodal points may comprise one or more main routes that coincide with the provision of a distinctive public space, containing a notable landmark building.

3.1.12 Often, two or more of these elements will need to be considered in combination to design effective legible environments e.g. designing a view towards a landmark or building that acts as a focal point or terminating feature, helps to create a sense of place.

Successful healthy places:

• Contain landmarks, such as important buildings, distinctive public spaces, public art, mature trees and views to these features.

• Distinguish important nodal points or junctions with distinctive spaces, often associated with activity and movement.

• Incorporate movement along conspicuous routes and edges that are easy to recognise and follow, such as main roads or defined streets.

• Allow for low traffic neighbourhoods where streets can become places and pedestrians have priority over the car.

3.1.13 Thresholds to private areas such as courtyards should use devices such as changes in surface, pillars, access through an archway etc. to define the extent of the defensible space. Psychologically, this gives the impression that the area beyond is private.

Healthy Living: Underlying Climate change principles of placemaking

Zero Carbon

Through the Climate Change Act 2008, and as a signatory of the Paris Agreement, the UK Government has committed to reduce emissions by at least 100% of 1990 levels by 2050 and to pursue efforts to limit temperatures to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

Net zero refers to a state in which the greenhouse gases going into the atmosphere are balanced by their removal out of the atmosphere.

This means considerable changes in society, the economy and our relationship with the environment.

Successful healthy places:

• Aim to achieve high-performance net zero buildings, improving energy efficiency, and reducing energy demand.

• Provide sustainable mobility including public transport and infrastructure for ultra-low emissions vehicles.

• Reduce land-based emissions, and regenerate biodiverse landscapes for nature and climate.

• Utilise the potential for renewable heating and electricity to meet our energy needs.

Active Travel

Active Travel England (ATE)'s strategic aims are to increase levels of walking and cycling to 50% of journeys in towns and cities by 2030. Creating better streets and networks for cycling and walking are the 'key design principles' as set out in the Dept of Transport's guidance, Gear Change: a bold vision for cycling and walking and the accompanying Local Transport Note (LTN 1/20) on cycle infrastructure design (July 2020).

ATE have developed a suite of tools based on the above national guidance to support the development of designs and the assessment of design quality for active travel interventions and schemes. The tools allow for route checks and area checks against a series of design criteria including:

• accessibility,

• comfort,

• directness,

• attractiveness

• and cohesion.

As well as cycle infrastructure design LTN 1/20, the suite of tools take forward the best practice found in Inclusive Mobility: Making transport accessible for passengers and pedestrians, (Dec 2021), Manual for Streets (2007) and Manual for Streets (2010), and existing street assessment tools, such as Cycle Infrastructure Design: Appendix A - Cycling Level of Service.

Walkable neighbourhoods

At its heart, this is an urbanism concept, a framework rather than a specific plan: trying to gradually change cities so people live relatively close to shops, workplaces and other amenities.

With this comes an inevitable shift from car trips to walking, cycling and public transport.

The principle of walkable neighbourhoods have been adopted by Local Planning Authorities such as Oxford and Newham. Research into their success is currently underway.

The Council supports this principle and will aim to create neighbourhoods that deliver the ability for residents to live close by local facilities.

Wayfinding

Wayfinding in townscape design requires designs that help individuals orient themselves and navigate environments with ease. This involves embedding visual and spatial cues-such as distinct landmarks, consistent signage, spatial hierarchies, and memorable streetscapes. The aim is to facilitate intuitive movement and decision-making.

3.1.14 Safer neighbourhoods

The movement network should be designed to create a safe and comfortable environment for users

3.1.14 Routes should be clear, direct and attractive places where people feel comfortable. If they are cramped, poorly overlooked, indirect or unwelcoming they can attract crime or anti-social behaviour and discourage legitimate users.

3.1.15 Walkable neighbourhoods

Proposals should seek to create walkable neighbourhoods that provide for or are located within easy walking distance of local facilities

3.1.16 A walkable neighbourhood is a residential or mixed area with a range of everyday facilities within an approximate 10 minute (800m) walking distance. Some facilities command greater catchments although these become less accessible on foot with increased distance.

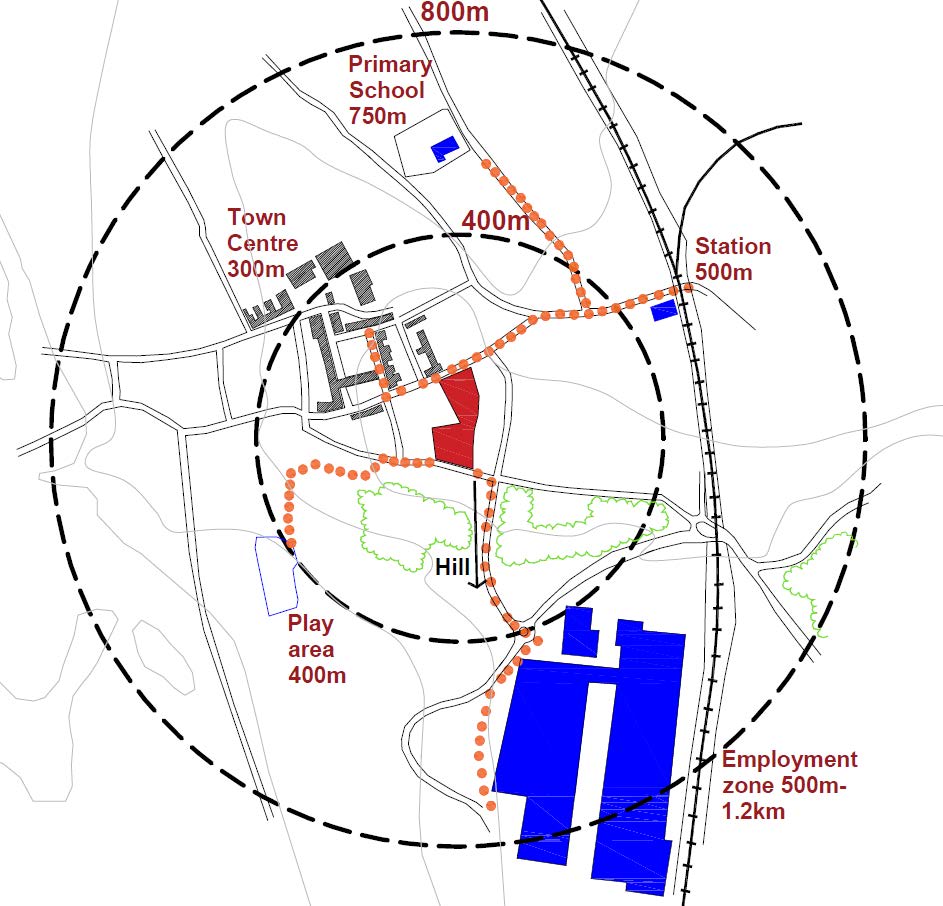

3.1.16 The catchment distances diagram on page 31 shows typical desirable and possible maximum thresholds for walking to facilities at local, neighbourhood/ village and settlement/ town level.

3.1.17 It is reasonable to expect some types of facilities, such as a children's playground to be within a short walking distance of a residential area, whereas people are prepared to walk further to reach other key facilities such as a local centre or a school.

3.1.18 These distances are a starting point for discussion. In more rural settings greater distances to more significant facilities (e.g. leisure centre, FE College etc.) are to be expected.

3.1.19 Accessibility criteria should also have regard to a range of local factors:

• The catchment populations of different facilities.

• The degree of permeability/ directness of walking/cycle routes.

• The general shape of the settlement.

• The propensity of users to walk to specific facilities.

• The influence of topography.

• The safety of the route (real or perceived fear of crime).

• The level of hostility in terms of traffic speed and volume and the quality of the pedestrian experience.

Indicative catchments:

• Toddlers play area (100-200m)

• Allotments (200-400m)

• Playgrounds and children's play/kick about area (300-400m)

• Bus stop (400m – reasonable and most convenient distance)

• Bus stop rural (400-800m – maximum less convenient/likely walking distance)

• Local park/natural green space (400-600m)

• Access to green network (600-800m)

• Local centre/shop (600-800m)

• Pub and village hall (600-800m)

• Primary school (800-1000m)

• GP Surgery (800-1000m)

• Playing fields (1000-1500m)

• Secondary school (1500-2000m)

• Town district centre or supermarket (1500-2000m)

• Leisure centre (1500-2000m)

• Industrial estate (2000-3000m)

• Major natural green space (2000-3000m)

• FE College (3000-5000m)

Source: Adapted from Barton et al, Shaping Neighbourhoods, 2021

Successful healthy places:

• Create active streets that are easy for people to find their way around and that link to local destinations.

• Are well lit and overlooked by surrounding buildings and used to provide a sense of natural surveillance and safety.

• Demonstrate clear definition between public and private spaces.

• Provide for pedestrians, cyclists and vehicles within the same space, without them being segregated.

• Avoid networks of separate footpaths and unsupervised areas, including public footpaths that run to rear of and provide access to properties, for reasons of safety and security.

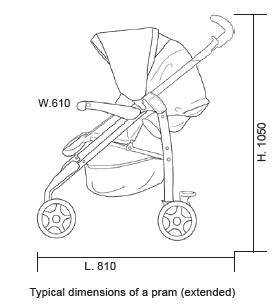

3.2 How to achieve easy inclusive walking design within residential schemes

3.2.1 "At approximately 200 journeys per person a year, walking is remarkably constant from cities to small towns. Only in rural districts do people walk significantly less than this." - CIHT Planning for Walking (2015)

3.2.2 Within Bolsover many new housing areas are located on the edge of settlements. This involves the creation of new walking routes. It is important to link with existing streets and create as much permeability as possible so that people can access local facilities. It is also important to ensure connections to the local countryside footpath network. Many people choose to live where they have access to both central areas and the countryside.

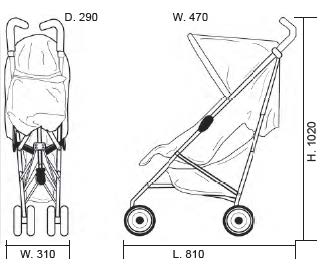

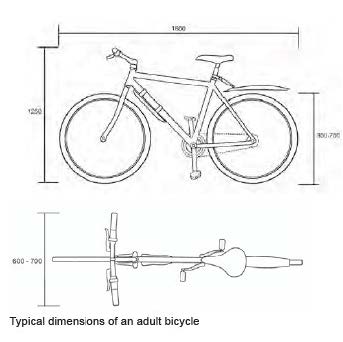

3.2.3 There is also a need to provide more accessible routes that are inclusive, making it comfortable and easier for people of all ages and abilities. In particular, consider wheelchairs and mobility scooters, people who need to rest occasionally, and mothers with pushchairs. Try to consider how junctions can be made easier, and how to prevent pavement parking. The '5Cs' of good walking networks should be considered. See opposite.

Infrastructure to improve pedestrian safety:

• Adequate footway and footpath widths.

• Kerb line build-outs to minimize the time taken to cross carriageways and slow traffic.

• Preventing parked vehicles blocking footways. Either through enforcement (signage) or physical means –use of tree pits and grills,

• Good pedestrian access to public transport

• More crossings which provide effective pedestrian priority.

• Fully understanding the use of tactile paving at crossings and the use of warning and guidance paving.

• Understanding how to make obstacle free routes for hard of seeing people.

• Fully protected pedestrian phases at traffic lights.

• Median pedestrian refuges.

• Use of 20-mph speed limits.

• Using street furniture and calming to give visual clues when to slow down especially where potential convergence of cyclists and pedestrians.

• Use of pedestrian friendly paving surfaces that are well drained

• Use of well-placed wayfinding to provide interest and encourage walking to destination points by providing direction and mileage markers.

The "5Cs" of Good Walking Networks

• Connected: Walking routes should connect all areas with key "attractors" such as public transport stops, schools, work and leisure destinations. Routes should connect locally and at district level, forming a comprehensive network.

• Convivial: Walking routes and public spaces should be pleasant to use and allow walkers and other road users to interact. They should be safe, inviting and enlivened by diverse activities. Ground floors of buildings should be continuously interesting.

• Conspicuous: Routes should be clear and legible, if necessary, with the help of signposting and waymarking. Street names and property numbers should be comprehensively provided.

• Comfortable: Comfortable walking requires high- quality pavements, attractive landscapes and buildings, and as much freedom as possible from the noise, fumes and harassment of vehicles. Opportunities for rest and shelter should be provided.

• Convenient: Routes should be direct and designed for the convenience of those on foot, not those in vehicles. This should apply to all users, including those whose mobility is impaired. Road crossings should be provided as of right and on desire lines.

Transport for London: "Improving Walkability: Good practice guidance on improving pedestrian conditions as part of the development opportunities," (Sept 2005) (Edited) and Planning for Walking Toolkit (March 2020).

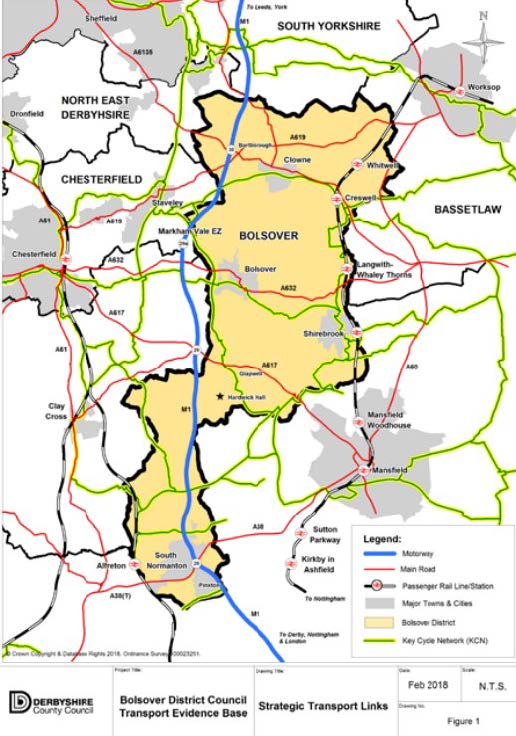

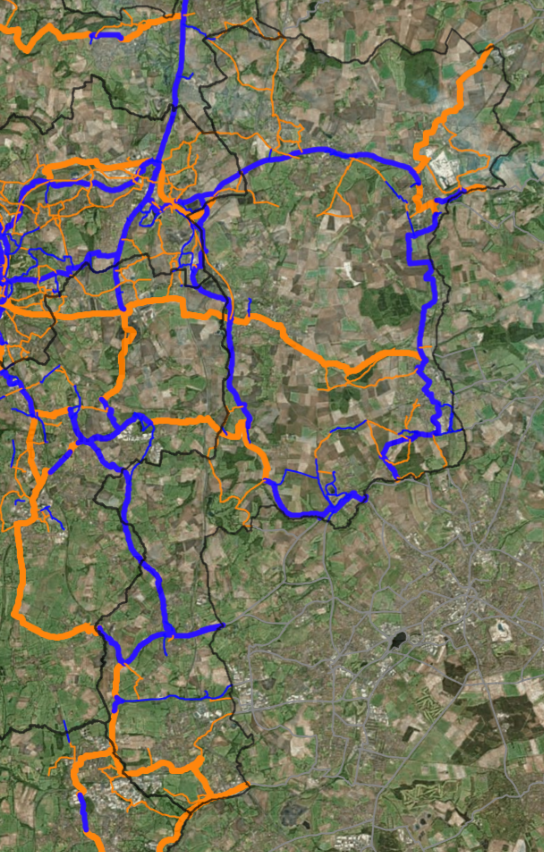

Countryside Multi User trails and cycle routes

The existing cycle network provides the opportunity for development sites to encourage cycling through providing links. Use the Derbyshire County Council mapping portal to identify local countryside routes.

Key:

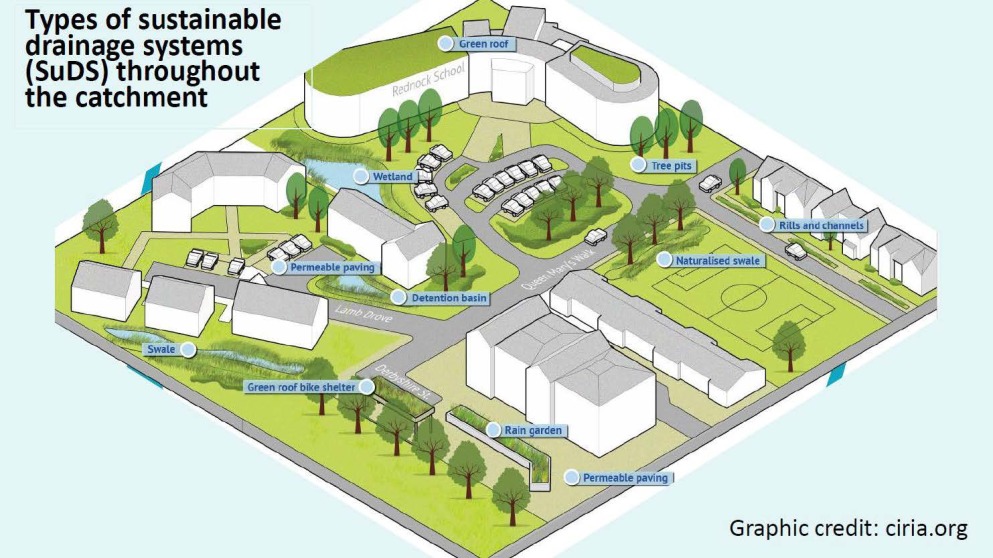

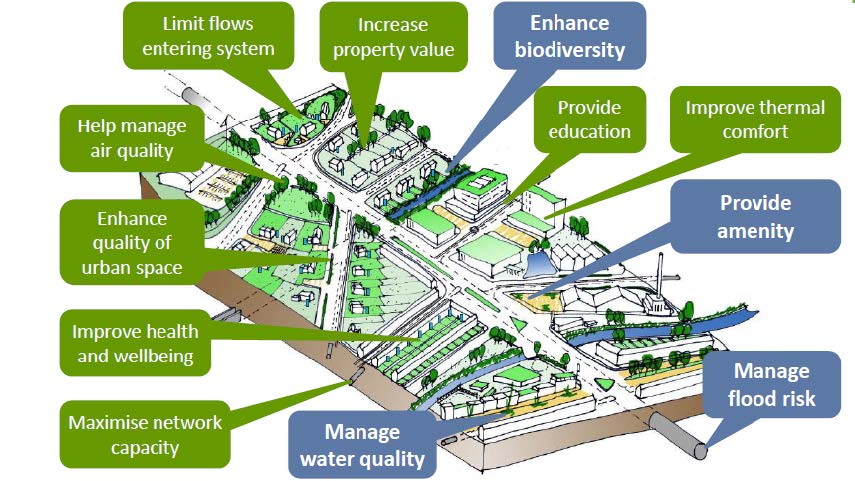

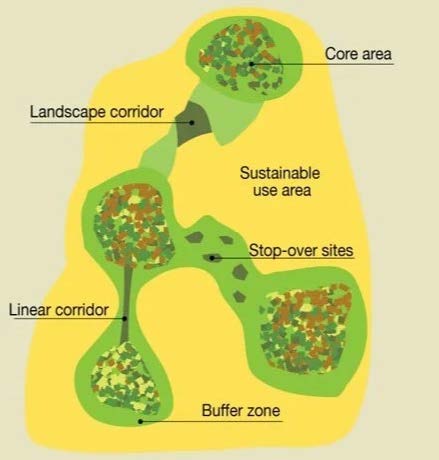

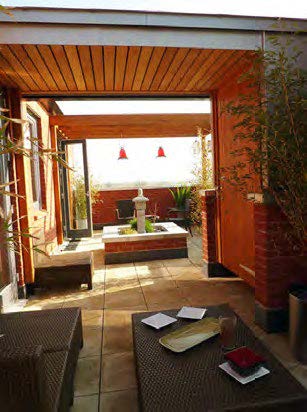

3.3 Green and Blue Infrastructure

Proposals should integrate green and blue infrastructure into the development layout wherever possible

3.3.2 Green and blue infrastructure refers to the network of existing or new, natural and managed green spaces and water bodies, together with the linkages that join up individual areas as part of a wider network of green spaces, such as footpaths, cycle paths and bridleways.

3.3.3 It provides many benefits, including:

Good Health – Greenery promotes health, well-being and enhances quality of life.

Recreation – Formal and informal spaces provide places for exercise and relaxation.

Liveable places – Green networks can add distinctiveness, a positive outlook or buffer negative features. They can also protect the setting of heritage assets and aid the interpretation of assets such as archaeology.

Movement – Pleasant recreational routes that link to adjoining green spaces.

Environment – Influence local microclimate and air quality, shade, shelter.

Water Management – green networks able providing to form part of sustainable urban drainage systems (SuDs).

Ecological Value – through the creation of habitats that support biodiversity.

Local Food Production – through provision of allotments, fruit trees/orchards, community gardens etc.

3.3.4 Green and blue infrastructure should be an integral aspect of the layout planning and structuring of any housing development wherever opportunities allow. This means retaining and incorporating natural assets such as mature trees, hedgerows or watercourses, as key features of the layout, if appropriate, or create new ones.

3.3.5 Emphasis is also placed on spaces being multi-functional e.g. a SuDs with swales and ponds can enhance the character of a development, have biodiversity and landscape value and be part of a network of recreational routes.

3.3.6 In all cases proposals should forge links with the wider network of green spaces whenever opportunities allow.

Successful places:

• Integrate existing green and blue features into their design/layout or create new ones.

• Connect with the existing wider green and blue infrastructure network.

• Create multi-functional green and blue spaces and routes.

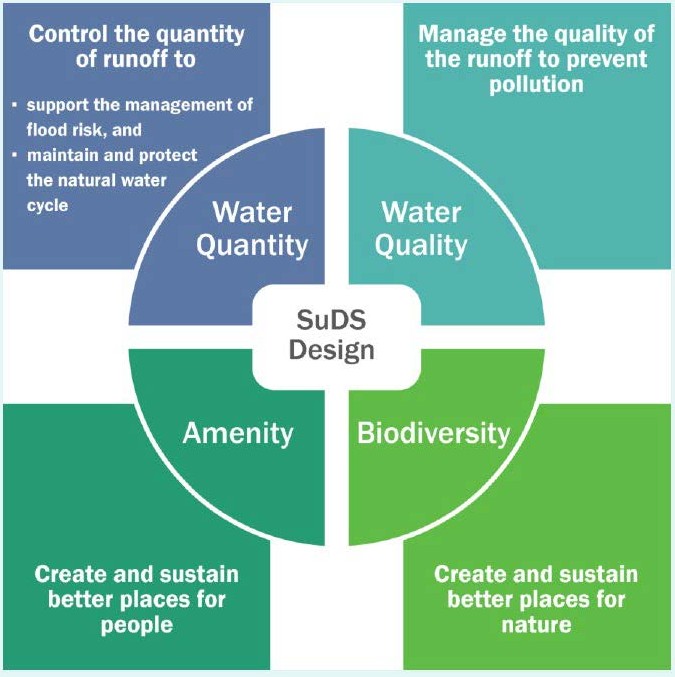

The Key Principles of SuDS Design

SuDs benefits

Street Solutions:

• Rain gardens

• Hydro planters

• Pavement Crate

• Systems.

Plot solutions:

• SuDs pods and

• Planters aid

• Biodiversity enhancement.

3.3.7 An edge of settlement development that fully integrates a network of green and blue infrastructure into its layout. Existing positive natural features have been retained and incorporated wherever possible. New green elements (swales/ponds, street trees, green spaces/corridors etc.) are multifunctional features, forge links with the surrounding area and add value.

Examples of Characterful SuDs Design

3.4 Townscape

3.4.1 Townscape

Schemes should be designed to create places that positively contribute to the built environment by enhancing the townscape and visual amenity. Developments should provide a clear benefit to the locality.

3.4.2 Townscape design knits buildings together with the spaces and elements that surround them – landscape, paving, and open spaces. It's the skilful arrangement of these environmental components to create a cohesive urban scene. This scene should be aesthetically pleasing in its relationship between built form and open spaces, and functionally successful for its intended purpose.

3.4.3 All schemes should create places that contribute to local identity and character, adding beauty to the townscape and promoting a sense of identity. This alongside ensuring good design and implementation, will determine whether a scheme adds positively to the richness and interest of the townscape and supports more vibrant neighbourhoods.

3.4.4 Often the places we find most interesting have developed incrementally providing layers of texture and form that while sometimes haphazard, combine to create attractive townscapes. Occasionally, a carefully planned scheme may exhibit similar qualities. However, the art of townscape is frequently undermined by the standardisation of housing with an emphasis on utility, economy and function, limiting the potential for incidental occurrences to stimulate, surprise or delight. Often the result is monotonous and uninteresting.

3.4.5 It should be the aim of those involved in the development process to ensure that the design of their proposals creates new townscape that is a meaningful and worthy addition to the settlement.

• Contribute positively to the richness and interest of the settlement to foster a sense of place by applying the good urban design practice principles (places not estates).

• Respond to the individuality of places in respect of local characteristics such as building forms, materials, traditions, street patterns and spaces to inform the approach to the design.

• Establish a clear urban structure within the built form, streets and spaces.

• Use the relationship (juxtaposition) of buildings, streets and spaces to form varied and interesting townscapes and a sense of identity.

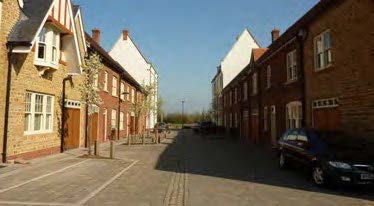

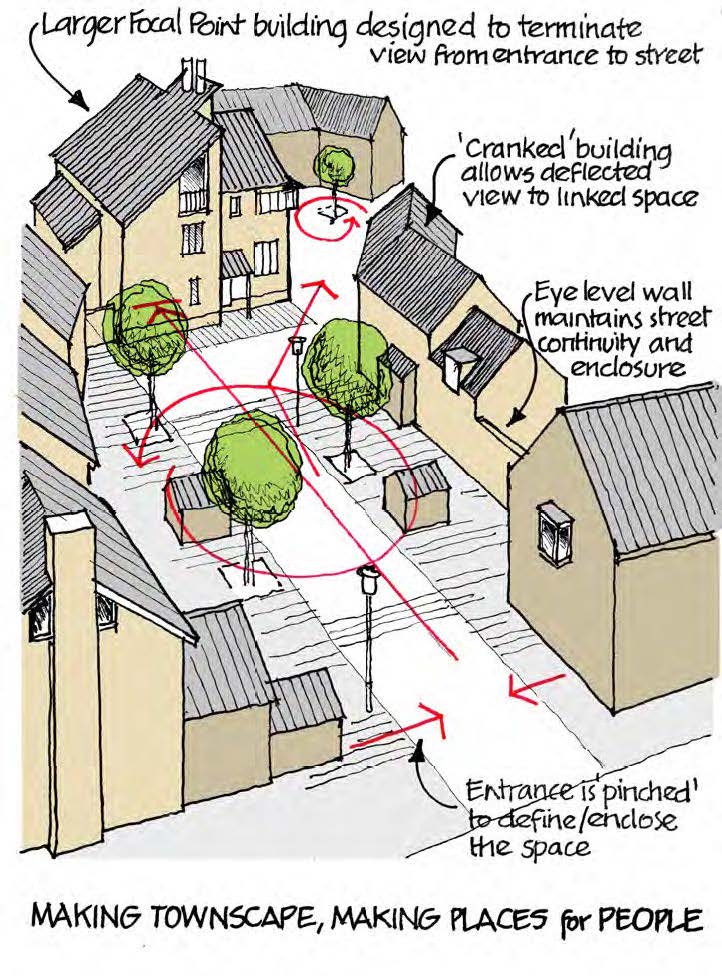

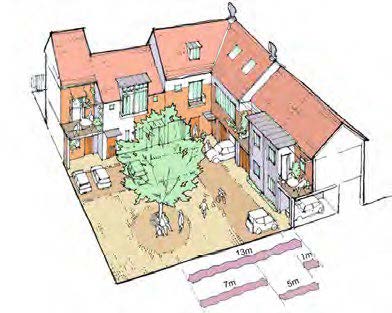

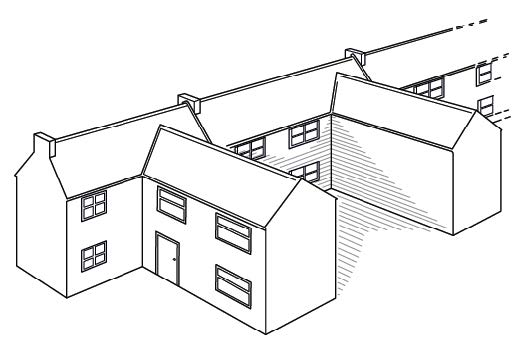

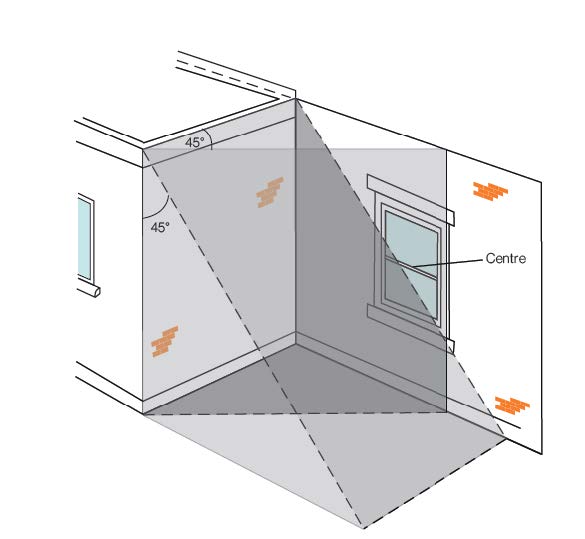

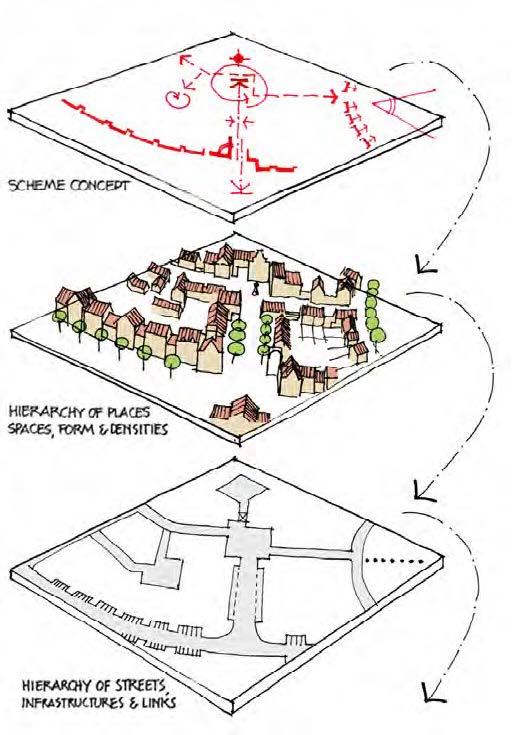

3.4.6 Considering the development as a three dimensional composition enables the designer to carefully integrate the different elements of the built environment as a coherent design. The example shows how:

• The entrance is narrowed to create a ‘pinch point’, signaling drivers to slow upon entering the street and encourages vehicles to emerge with caution.

• The buildings have been arranged to define the edges of a space, provide continuity and create a strong sense of enclosure.

• Buildings are outward looking with windows orientated to overlook the street, providing safety and security also at gateways.

• A larger building is positioned deliberately on the axis of the street to provide a focal point and ‘terminate’ or ‘close’ the view from the entrance.

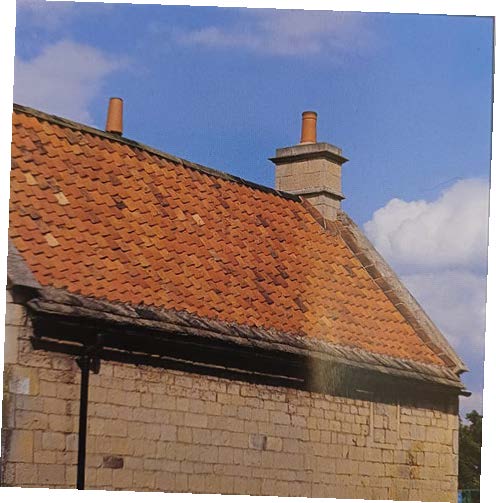

• Roof heights (eaves and ridge) and roof forms, together with chimneys and dormers add visual interest to the skyline. Stepped changes in roofscape provides a varied profile.

• Street trees provide shade whilst softening the appearance and giving visual appeal. They are used to define spaces.

• Hard surfacing strengthens pedestrian area prompting drivers to slow down and marks areas of on-street parking.

• The ‘cranked’ building uses the built form to deflect a view into to a rear courtyard, which itself incorporates a feature focal point tree.

3.5 Character

3.5.1 Character

Developments should create places of more distinctive character based upon an appreciation of the site and surrounding area, responding positively to its natural and built context.

3.5.2 The concept of character relates to the qualities belonging to a place that together give it its own identity and help distinguish one place from another. This is often referred to as its sense of place; so when you get 'there', you have a sense of arrival or being 'somewhere'.

3.5.3 Character is influenced by factors such as architectural style, materials and traditions, relationship of buildings to landscape, history and economy. These factors combine to create places that are distinctive and specific to their location, not the qualities of somewhere else.

3.5.4 New housing development is often seen as bland with little character, and unable to respond positively to its context. Many fail to create any sense of place and feel disconnected from their locality; essentially they could be 'anywhere'.

3.5.5 Designs should 'ground' developments to their location, to help foster a sense of place, character and connection. This requires an approach that goes beyond the unthinking application of standard solutions, but instead seeks to understand and respond meaningfully to the context, site conditions, community values and needs.

3.5.6 Locations with a weak or negative character can provide few contextual clues or positive features to build on. In these instances designers should draw inspiration from positive aspects of the wider context to design proposals that are appropriate to the locality, rather than recreate an existing poor design.

3.5.7 In some circumstances the design of a proposal may depart from the local context and character (although it should not be ignored). For example, a highly energy efficient design may have particular requirements. Such proposals must be explained and justified and will be assessed on their individual merits.

Successful places:

• Strengthen their setting by responding to topography, landscape character and edges.

• Create strong character areas by responding to settlement street patterns, density, layout, built form, materials and details.

• Relate the height, massing and scale of development to that nearby to create an appropriate relationship with adjoining areas. (Variety within the built form will be encouraged in respect of townscape/place hierarchy considerations – see 3.12).

• Encourage local distinctiveness in materials, architectural details, building techniques and styles.

3.5.8 Local distinctiveness

Developments should enhance local distinctiveness by taking the opportunities available to carefully integrate the proposal into the site, its setting and the way it relates to existing buildings.

3.5.9 Local distinctiveness relates to places, their qualities and people’s attachments to them. It is both physical and cultural and can seem intangible, yet we are able to recognise its appeal when we see it. However, the interest and richness of places is diluted with standardisation and the associated loss of the integrity and detail that people value.

3.5.10 Local distinctiveness has many layers, but it is about more than just variety. There is no single formula to define it, as by its nature it must be determined according to each place. The report 'Distinctly Local' 2019, has identified how to address the distillation of place, understanding boundaries as defining characteristics, the threshold to surrounding landscape, reinventing traditional building forms and how to create a narrative for new building forms.

Detail – Detail in everyday things is important. People respond to subtle signs that add layers of richness and meaning to a place. The folds in a local field, a window or door detail, a local building tradition, all stimulate our senses and develop meaning.

Authenticity – The real and the genuine hold a strength of meaning for people, whereas the inauthentic appears one dimensional and unsatisfying. Local distinctiveness is not necessarily about beauty but it must be about integrity. It can also coexist with crafted experiences, as long as there's a sense of genuine connection to the place's history and character.

Particularity – The special or rare aspects of a place may be important, but it is the qualities of the common place that define its identity. The focus should be on appropriateness to and expressiveness of the time and place, rather than simply being pre-occupied by difference. The "commonplace" is wide including elements like community gardens, repurposed spaces, or even the way a certain street functions.

Patina – Age has to be recognised as having been gathered. Remnants of the accumulation of activity, the layers or fragments of a place experienced, can be added to, without resorting to their loss, damage or crude interventions. Common Ground (Losing Your Place, 1993).

• Complement their context by using the intrinsic landscape of the site and the surrounding area to inform the approach to the layout of a scheme.

• Use natural landscape features such as mature trees, hedges, watercourses, ponds, rock outcrops, areas of ecological value to enhance the site and setting.

• Retain, reuse and enhance buildings, structures or features of historic, archaeological or local interest and their immediate setting where appropriate.

• Utilise locally relevant materials associated with the landscape character area in which the site is located.

• Retain and utilise architectural features from existing buildings, structures or features if these are unable to be retained for structural or viability reasons (this must be justified).

• Recognise and retain important views.

3.5.11 Character Areas

Where appropriate to the scale of development, proposals should be sub-divided into areas of character the design of which is based upon clearly defined characteristics

3.5.12 In larger scale developments character areas may be devised to differentiate between different parts of the site, assist legibility and avoid large areas of repetitious housing.

3.5.13 Proposals should assess whether the site relates to an existing area of particular character and determine how the scheme can introduce areas that strengthen character and reinforce local distinctiveness. This may influence the mix of uses, density and pattern of development, views to existing landmarks, the network of routes and open spaces, urban form, materials or other factors.

3.5.14 There may be opportunities to introduce new elements or character areas, particularly if a place has a weak, unremarkable character. However, the context (immediate or wider) should normally provide the starting point to developing the principles that will define a character area, with the aim of strengthening the distinctiveness of the settlement and being appropriate to the place.

3.5.15 Character areas should not be artificial creations or based upon alien designs or features from elsewhere, otherwise they will appear 'forced' and inauthentic. Instead they should be a genuine response to the place, its characteristics, constraints and the distinctive qualities of the area. This will provide integrity and reinforce local identity.

3.5.16 The basis of each character area should be informed by a street and place hierarchy (see sections 3.6 and 3.12) and each area should have a genuine role to play in the creation of a movement network and the character of the place. The street hierarchy itself should be informed by the context and what is appropriate in any given setting. This can be determined through the site context appraisal process (see Part 2).

Above: Three distinct streets within the same development demonstrate that areas of differing character can be formed without resorting to large areas of monoculture housing

Successful places:

• Respond to the naturalness of the site, its landform and any distinct features.

• Are sensitive to the characteristics of the local area, including building forms, details, layouts, edges, boundary treatments.

• Vary or grade densities (influenced by factors such as location within the site, land uses and access to transport etc.)

• Are influenced by prevailing land uses (existing and proposed).

• Incorporate local materials, details and building methods.

• Are appropriate in scale, height and massing with regard to adjoining build Ings and general heights in the area, views and local landmarks and topography and visual impact.

• Provide a positive relationship with the edges of the site including any areas of open countryside.

3.5.17 Establishing the place and street hierarchy will begin to inform the characteristics of each character area.

3.5.18 Using more than one developer or employing more than one architect to design different aspects of a scheme will also support the creation of character areas.

Metalwork images by James Price Blacksmith (blacksmithdesigner.com)

Parameters to define character areas should include:

• Street type and width;

• Building use/house types and street continuity (density/intensity of development);

• Building set-backs;

• Building height and enclosure;

• Front boundary treatments;

• Topography and landscape;

• Materials and architectural attributes.

Heritage and Retrofitting Existing houses

'Adapting Historic Buildings for Energy and Carbon Efficiency'. Historic England Advice Note 18 (HEAN 18), provides guidance on approaches to improve the energy efficiency and support carbon reduction of historic buildings, whilst conserving their significance. Historic England advocates a whole building approach when considering adapting historic buildings, based on:

• An understanding of the building and how it performs;

• An understanding of the significance of a historic building, including the contribution of its setting;

• Prioritising interventions that are proportionate, effective and sustainable; and

• Avoiding and minimising harm and the risk of maladaptation.

For listed buildings check 'The list' entry hosted on the National Heritage List for England. The List description is for the purpose of identification. It does not define the significance of the building as a heritage asset. A Statement of Significance should be undertaken that draws upon a detailed building's survey identifying stages of development and associated significant features. The Statement should include reference to relevant archive documents.

Conservation Area Appraisals are also key to understanding a buildings significance, outlining the history and development of an area. The appraisals also identify buildings of significant local interest (unlisted buildings of merit).

Prepare an Energy Plan for the building by a qualified energy specialist. Check for any free advice or services available. Derbyshire councils periodically currently provide free Home Energy Plans for properties in Conservation Areas, where the PCR is below 'D' or for off-gas hard to reach properties.

As a general rule, small-scale interventions should be considered before more substantial ones and should be reversible where possible. Multiple interventions should be based on a holistic and phased approach. Don't assume all energy interventions will be given planning approval. A balance will need to be made between the impact of the intervention and the heritage significance of the building, and the level of public benefit. Where possible, any opportunities to reveal or improve the significance of the building should be considered.

• Draught proof windows and doors using products that respect the character of the original building and area.

• Wall and Roof insulations that are harmonious and complement the original building and streetscene. (Internal and external resulting in a more breathable functioning building).

• Improved ventilation through use of discreet roof tile ventilation or retained but decommissioned chimney stacks.

• Solar tiles on front roofs and in-roof or mounted solar panels on rear roofs based on visual impact.

• Decreet placing of heat pumps.

• Use of greening of walls and roofs where they compliment the buildings character of setting.

3.6 Layout

3.6.1 Layout

Layouts should provide a linked network of routes and spaces within the development and connect to adjoining areas

3.6.3 The pattern of routes, densities, uses, development blocks and individual plots influence the character and dynamics of a place. How it connects to its surroundings can also influence wider movement patterns.

3.6.4 Layouts based upon an interconnected network of streets and spaces encourage walking and cycling as realistic alternatives to the motor car and distribute vehicle flows more evenly, helping to disperse traffic.

• Comprise internally well connected layouts of routes and spaces.

• Create blended good access to adjoining areas, with links to existing streets and paths.

• Arrange layouts in a way that support the viability of local facilities.

• Carefully relate different uses, avoiding bad neighbour uses close to homes.

3.6.5 Variable Density

Depending on its scale and context, a development should provide variable densities to support areas of character, the viability of local services, facilities and the landscape setting of the area

3.6.7 Densities tend to decrease with distance from the centre, becoming less dense with a looser knit urban grain towards the settlement edges.

3.6.8 Rather than applying a uniform density, densities should be varied across the site area, where the scale of development allows and having regard to its particular circumstances and context.

3.6.9 Where appropriate, densities should be graded so that higher-density development supports the viability of facilities (local shops/high streets etc.) and services (such as bus stops/ public transport corridors/stations) where there is good pedestrian accessibility. This can also reduce reliance on private vehicles and the number of short trips taken by car.

3.6.10 Densities should normally be reduced towards areas of lesser activity with lower-densities along green corridors, towards settlement edges and against the countryside to assist with a graduated transition between town and country.

• Avoid uniform densities across the whole development.

• Arrange the layout and density of the development in a way that supports the viability of existing or proposed local shops, amenities and public transport by providing good connections to facilities that encourage walking and cycling and reduce the number of journeys and distance travelled by car.

• Incorporate areas of differing density according to the location and character area of the site.

Urban

Suburban

Village

Rural

Above: Density and urban grain will vary according to the type of settlement, whether town or village, and the location of the site within the settlement. Generally this will decrease with distance from the centre of the settlement.

Slightly increasing the number and variety of homes in an existing neighbourhood, allows for densification while respect existing patterns of development. Gentle density allows the redevelopment of an existing site to include more multilevel houses/apartments or infill row houses. This optimises land use and offers a variety of housing typologies without changing the neighbourhood's character and feel. The concept of 'gentle density' allows for generational change as communities grow and evolve. Bolsover District will encourage innovative schemes that allow for increases in gentle density. This may involve pockets of increased density and height in more suburban areas.

3.6.11 Street Hierarchy

Developments should provide a hierarchy of street types that contributes to the creation of a sense of place and facilitate movement, rather than a hierarchy that is determined primarily by traffic capacity

3.6.12 The relationship between streets and the adjacent buildings strongly influences the safety, appearance and movement function of a development. The layout should accommodate traffic and allow for access by service vehicles, but it should also contribute positively to the character of the development.

3.6.13 Residential streets should not be seen simply as a conduit for traffic, but as places in their own right. Designs where parking and highway space are dominant should be avoided.

• Comprise a hierarchy of different street types that are appropriate to the place.

• Comprise streets where the character of the street and its movement function are given equal consideration (i.e. traffic needs are not assumed to take precedence).

• Ensure a considered relationship between the streets, spaces and adjacent buildings that provide their setting.

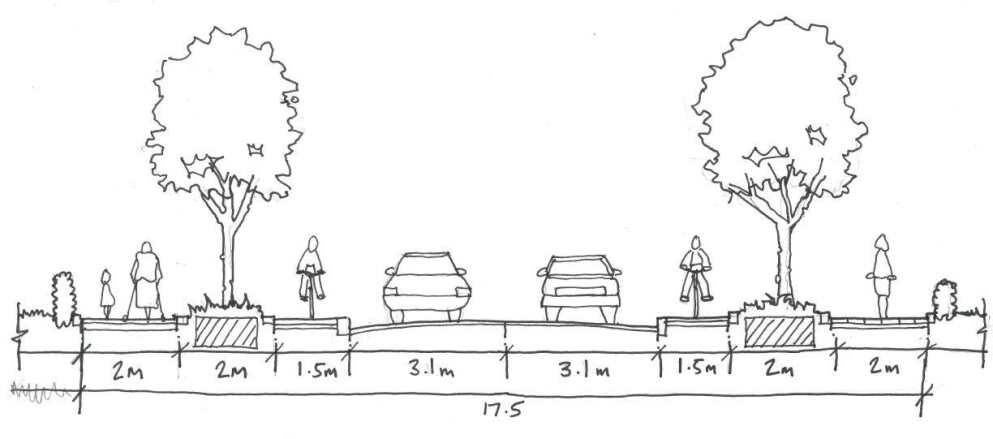

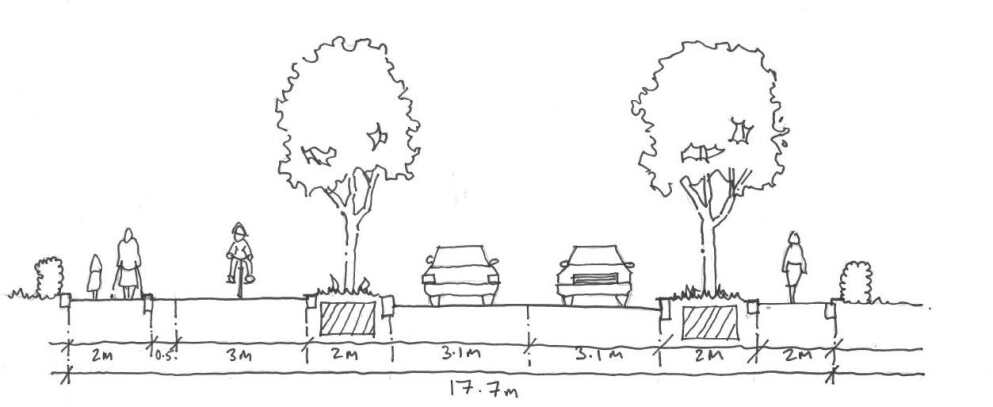

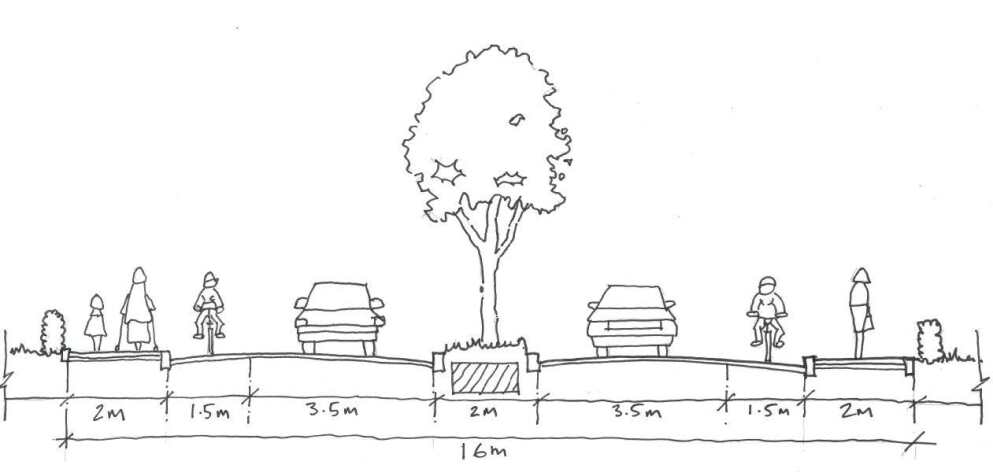

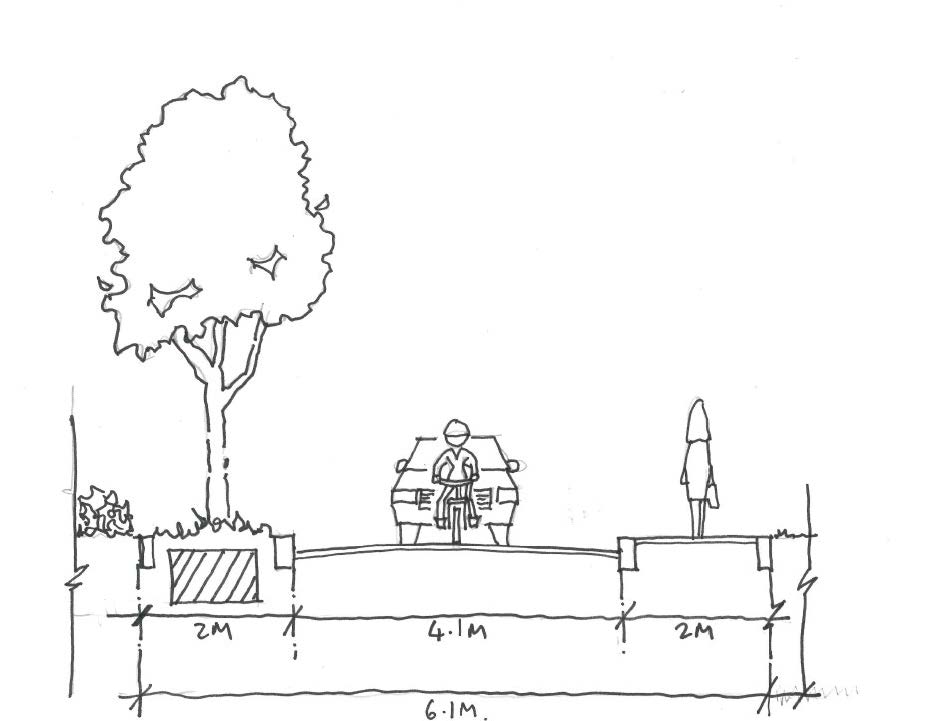

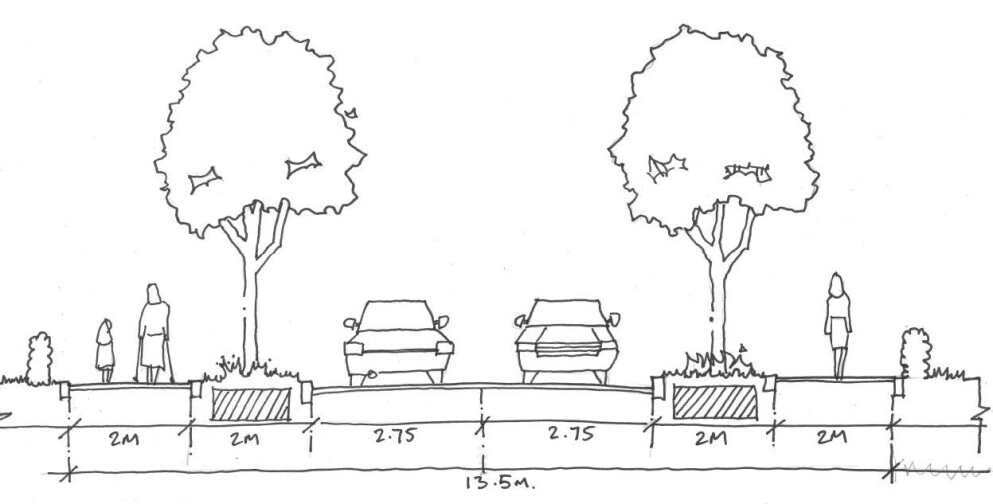

Street sections show a hierarchy of street types (Drawings courtesy of the Borough Council of Wellingborough and Matrix Partnership Ltd)

3.6.14 Crime Prevention

Layouts should be designed to help reduce opportunities for crime and anti-social behaviour

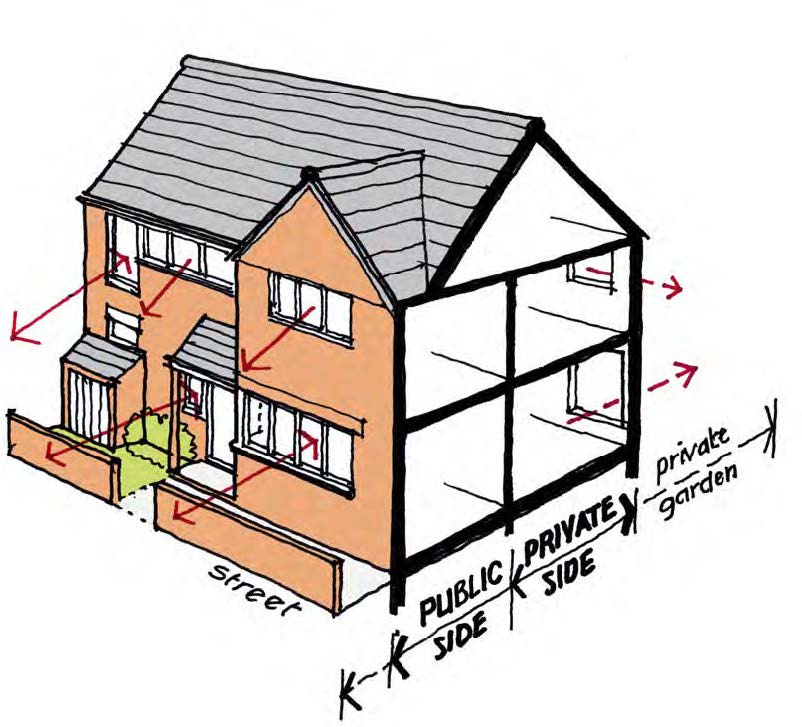

3.6.15 The design of the development layout can help to deter anti-social behaviour and reduce opportunities for crime. Ensuring clear distinction between public and private spaces, good overlooking from adjoining buildings, lighting and avoiding the creation of potential problem areas can all minimize the likelihood for future problems. Consult Secure by Design Homes Guide 2024.

• Design and orientate buildings to strengthen streets/spaces and provide active edges.

• Ensure any pedestrian and cycle paths are green, short in length, sufficient width to feel safe and comfortable, overlooked and lit.

• Routes should be direct and follow desire lines to places where people want to go.

• Normally avoid rear lanes and direct access to the rear of properties.

• On-plot and off-plot parking areas should be overlooked and relate well to adjacent buildings, without being dominant.

• Use boundary treatments to distinguish clearly between public and private space.

• Avoid potential problem areas such as awkward or poorly located public space.

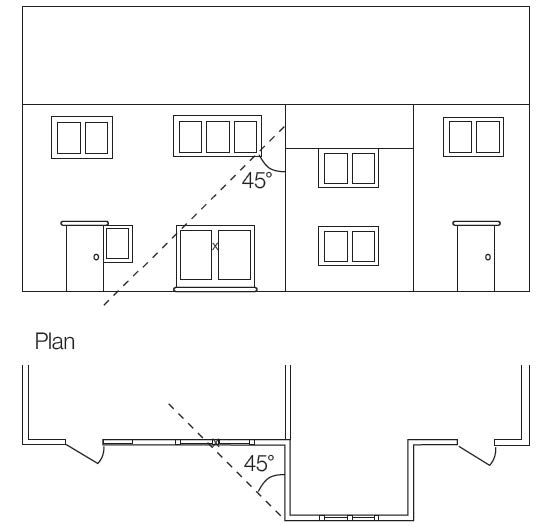

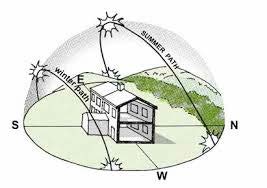

3.6.16 Passive Solar Design

Developments should be orientated to benefit from passive solar energy

3.6.17 Homes that benefit from passive solar gain use less energy for lighting and heating and generally provide a brighter and more pleasant living environment.

3.6.18 Where practicable, the design and layout of developments should seek to take advantage of passive solar energy. Orientating dwellings within 30 degrees of south is sufficient for them to benefit from year-round solar gain.

3.6.19 Developments should however avoid layouts that are designed entirely around achieving passive solar gain at the expense of other urban design considerations. Proposals comprising of largely south facing parallel streets will be unlikely to satisfy other important design requirements..

3.6.20 Larger south facing windows will absorb heat into the building while small north facing windows will help minimise heat loss. Shading may be required to prevent overheating in the summer. However, obstructions to south facing elevations should be limited in order to maximize the benefits from solar gain during the winter. Deciduous trees can be valuable by providing summer shade while allowing through low-winter sunlight.

3.6.21 Care is required to avoid overheating and building designs need to consider the occupants comfort. Homes with a high thermal mass (constructed from dense materials that can absorb heat) absorb solar energy and then slowly release it at night resulting in low temperature fluctuations within a dwelling. Buildings constructed from materials with a low thermal mass are susceptible to rapid extremes of heating and cooling, creating uncomfortable living conditions.

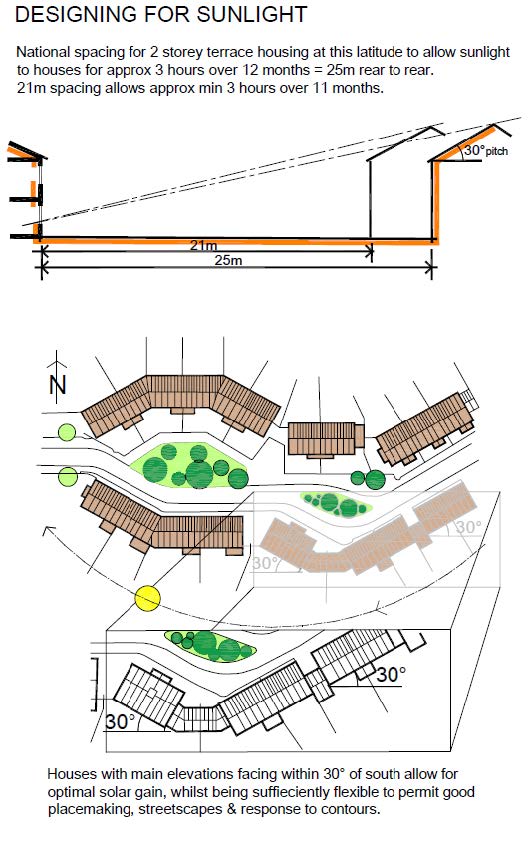

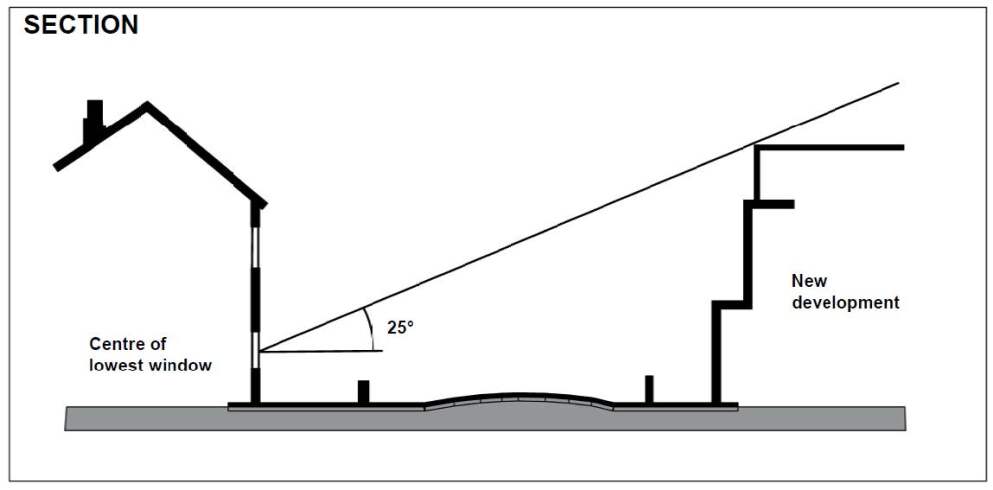

Designing for sunlight

National spacing for 2 storey terrace housing at this latitude to allow sunlight to houses for approx 3 hours over 12 months = 25m rear to rear. 21m spacing allows approx min 3 hours over 11 months.

Houses with main elevations facing within 30 of south allow for optimal solar gain, whilst being sufficiently flexible to permit good placemaking, streetscapes and response to contours.

REF: Site layout planning for daylight and sunlight. BREEAM UK New Construction (2022)

• Orientate dwellings within 30 degrees of south, where practicable.

• Seek to provide habitable rooms with a south facing aspect.

• Design to prevent summer overheating.

• Minimise obstructions to winter solar gain.

3.6.22 Settlement Edges

Developments that form a new long term settlement edge should create a positive relationship with the adjoining countryside, providing an appropriate transition between the built up area and the adjoining landscape

3.6.23 Development on the outskirts of towns and villages will have the effect of creating a new edge to the settlement. New edges require careful treatment to mitigate any visual intrusion and integrate schemes successfully into their setting.

3.6.24 A development's relationship with the adjoining landscape is critical to achieving an appropriate transition between town/ village and country and should be an integral consideration of the design layout.

3.6.25 A combination of careful building design, orientation and provision of effective landscaped areas will normally be required. This does not mean simply hiding the development with screen planting (although landscape buffer planting may sometimes be appropriate). It is about creating new edges that have a positive interface with the countryside. Depending on the scale of the development, a range of measures to ease the transition between urban and rural may be required.

3.6.26 Grading the density of development by reducing its scale and intensity towards its edges with the countryside, allows for planting within and between plots to create a featheredge to the settlement.

3.6.27 Wherever possible, layouts should be arranged so dwellings are orientated to be outward facing to address the countryside, rather than turning their back.

3.6.28 Where plot boundaries are located against the countryside they should normally comprise soft planting and reinforce the transitional qualities of the edge. Hard boundaries comprising only walls or fences will normally be inappropriate unless they are designed to reflect the rural character. They may also need to be combined with planting.

3.6.29 Developments may require substantial landscape buffer areas. These should normally be outside any residential curtilage/ownership with suitable long-term management arrangements put in place to ensure their future retention. Where existing trees and hedges are present these should be retained and reinforced by new planting, if necessary.

3.6.30 The extent of a landscape buffer area should be proportionate to the scale and impact of the development and may vary according to the prominence and sensitivity of the settlement edge, but may need to be substantial (e.g. 10 – 20m or greater) and should comprise suitable native species that reflect the landscape character.

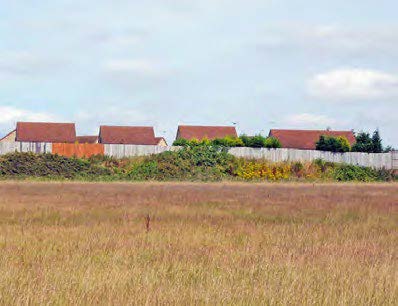

Above: Outward facing houses positively address the adjoining spaces and have been considered as a group to create an interesting composition and roofscape.

Above: Standard houses and layout result in a mundane roofscape and poorly maintained fencing creates an incongruous and abrupt edge treatment.

• Have regard to views towards the site from outside and mitigate any adverse visual impacts.

• Grade the scale and density of development to reduce towards the edges of the settlement.

• Orientate dwellings to be outward facing and address the countryside.

• Ensure the nature of any boundary treatment is appropriate to its rural character, avoiding abrupt walls or fences.

• Retain existing trees and hedges and incorporate new landscape planting within and on the edges of the development, utilising native species.

• Incorporate landscape buffer areas that are proportionate to the scale of the development and prominence or sensitivity of the settlement edge.

• Carefully consider the design of lighting schemes on settlement edges to minimise light pollution on local amenity and dark landscapes.

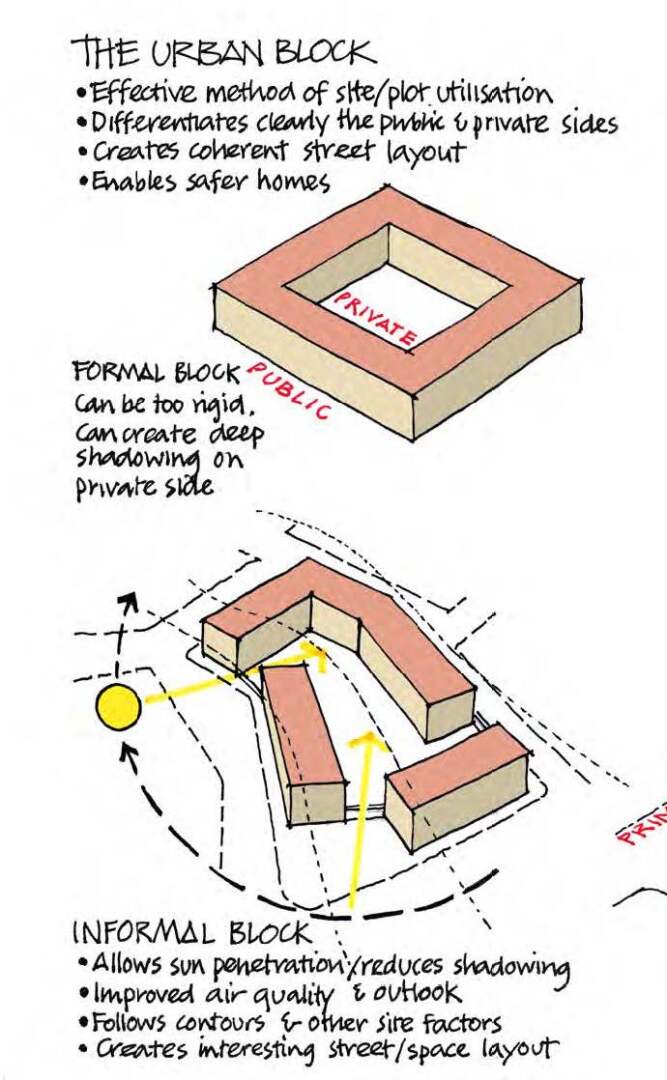

3.7 Block Structure

3.7.1 Block Structure

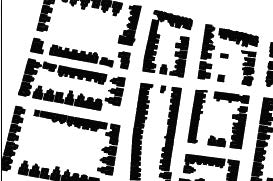

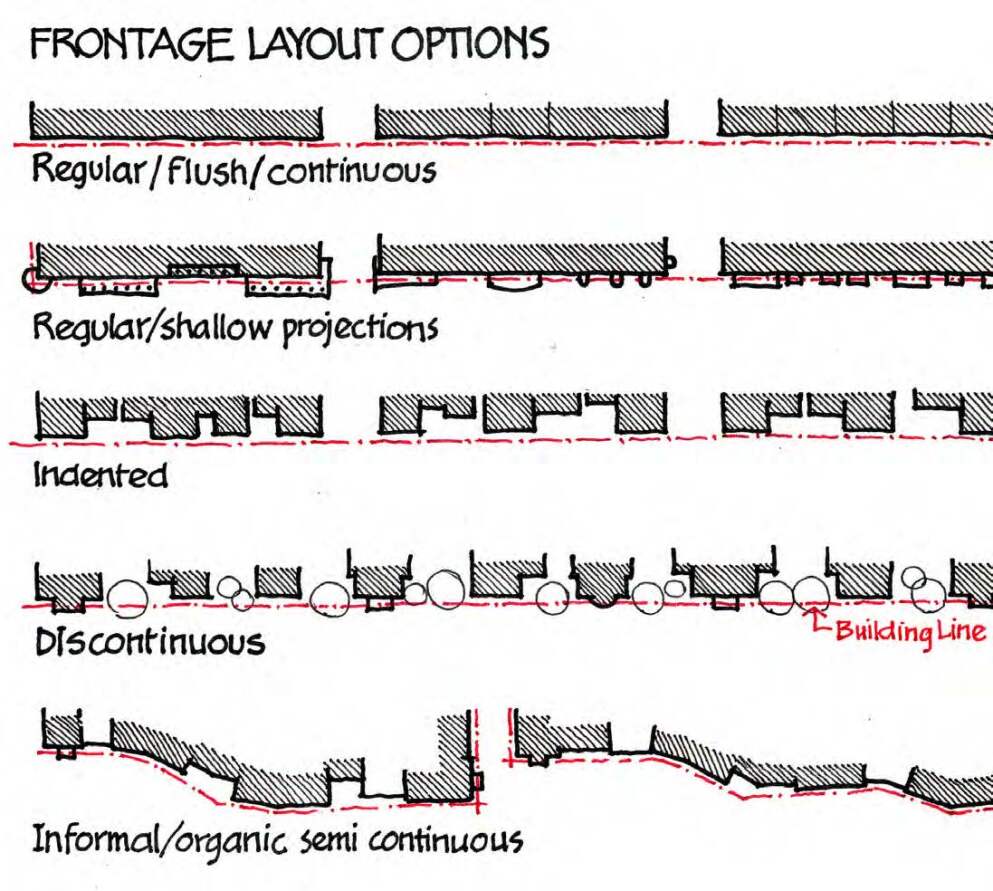

Layouts should be arranged in a pattern of perimeter blocks forming permeable streets with well defined frontages

3.7.2 The block structure is the pattern of development blocks contained within the overall layout.

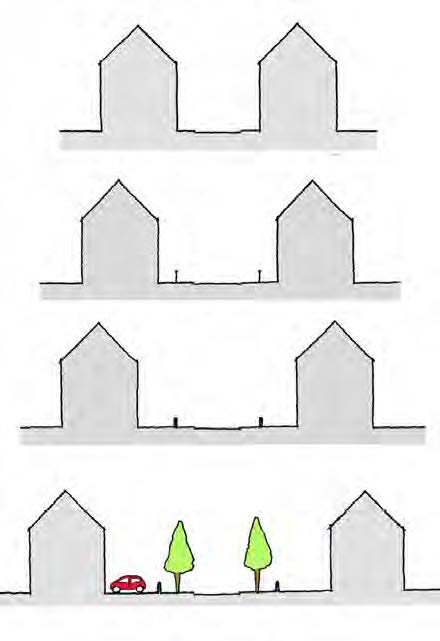

3.7.3 Perimeter blocks form connected layouts that create a walkable neighbourhood structure. This allows easy access throughout the area. Many places will already comprise a network of streets and blocks and these may be used to inform the approach to the design of the proposed block layout.

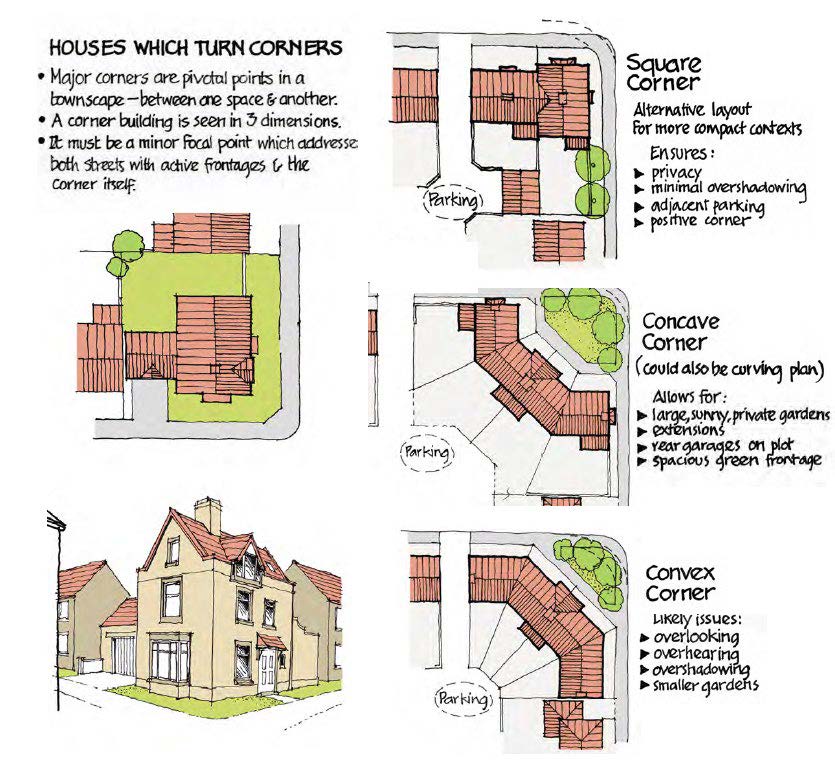

3.7.4 The design of blocks should not necessarily be uniform on all sides. The character of each side of the block should reflect the character of the adjoining street. Variation can also be achieved by making use of building types, appropriate mixed uses and designs that respond to corner locations

3.7.5 Depth of buildings are defined by adequate daylight. Central spaces are given over to private gardens, play spaces and public realm.

Successful places:

• Comprise layouts consisting of blocks that form a permeable street pattern. These can be a formal grid or have a looseness in composition.

• Design the pattern and shape of perimeter blocks to complement the site context and the character of the proposed adjoining streets.

• Block form can be interrupted with nodes and corners that are more distinct from the block arrangement and use orientation to allow light into internal courtyards.

• Include variation within each side of the block (density, height,

scale, use) to reflect the hierarchy and status of surrounding streets (main frontages, side streets, lane/ mews) and contribute

to the character, identity and function of each street frontage. Consider whether opposite corners need to relate to each other or not.

• Arrange development to be outward facing to overlook streets and public places with the primary access to buildings from the street via a clearly identifiable front entrances.

• Address key corners with special corner buildings or groups that address both sides of the corner with active frontages.

3.7.6 Block size and shape

The size and shape of blocks should form part of a permeable street pattern and respond to the conditions of the site

3.7.7 Perimeter blocks can be designed in numerous ways and may be formal or irregular. Key considerations when determining the size and shape of the block are:

• The permeability of the area (over-large • blocks can reduce permeability);

• Density;

• Parking strategy;

• Privacy and amenity;

• Daylight and natural ventilation;

• Topography;

• Potential uses of the block interior (if not private gardens);

Irregular block shapes can offer greater flexibility and be designed to:

• Respond to the specific conditions of the site (e.g. existing features or topography);

• Assist in slowing traffic;

• Optimise orientation for good light penetration;

• Create focal points and interest in the street scene;

3.7.8 Block sizes can vary widely, but blocks of 60-90m x 90-120m provide the optimum dimensions to support good pedestrian accessibility, vehicle movement and allow for sufficient back to back/back to side separation distances.

3.7.9 Larger blocks provide scope for incorporating an interior court that can accommodate a variety of uses, such as play, parking, communal gardens or off-street service areas. Alternatively they may be sub-divided by mews streets for access, to accommodate parking and improve permeability. Blocks with open interiors should be overlooked with managed access wherever possible.

Successful places:

• Ensure block sizes and arrangements are varied with frequent spacing (informed by the context).

• Ensure block shape responds to the site conditions, topography and the character of the surrounding area.

• Incorporate secure interior spaces (including private gardens).

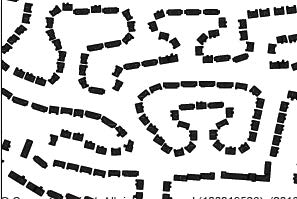

3.7.10 Cul-de-sac

The provision of cul-de-sacs should normally be avoided unless particular site conditions dictate that a cul-de-sac design is the most appropriate way to develop the site. In such circumstances this should be explained and justified

3.7.11 Layouts designed around a distributor road and cul-de-sac model have a number of disadvantages. However, in some circumstances, the provision of cul-de-sac designs may be necessary as a means of developing a difficult site or where particular constraints impose limitations that prevent connections being made.

Successful places:

• Avoid overlong cul-de-sac and ensure any through connections for pedestrians and cyclists are overlooked with active frontages to make them feel safe

• Avoid concentrating large volumes of traffic on a small number of dwellings.

• Design turning heads to form part of a space not just for turning manoeuvres.

• Ensure adequate parking is provided so turning areas remain clear of parked cars.

• Arrange the layout to avoid rear boundaries backing onto public street frontages.

3.8 Parking

3.8.1 Approach to parking

Parking provision should provide a balanced mix of parking solutions that are integrated into the design and layout to support its appearance without cars becoming visually dominant

3.8.2 Sustainable public transport can provide an alternative to or complement car use. However, car ownership is an established aspect of modern life and satisfactorily accommodating parked cars is a key function of most residential streets.

3.8.3 Designs need to reconcile the need to provide attractive streets that include adequate parking, but without detracting from the character or visual quality of the place. Well designed places integrate car parking without it becoming over- dominant.

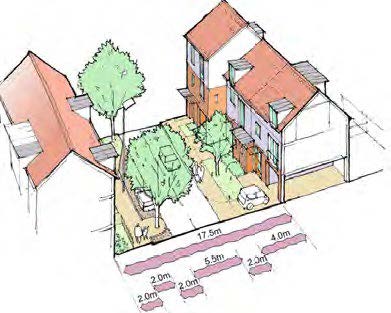

3.8.4 The drawing below courtesy of DSA Environment and Design Ltd shows a housing layout at Cornwater Fields, near Mansfield, incorporating a well-designed mix of parking solutions including on-plot provision, rear and forward parking courts and on-street spaces designed as part of the landscape strategy into the street scene.

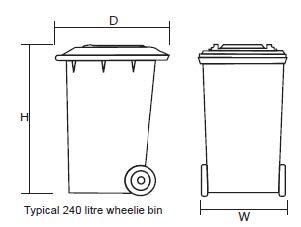

Bolsover District Council’s Standards for Parking including levels of parking and dimensions are found in the separate: Supplementary Planning Guidance: Local Parking Guidance, February 2024. This includes design guidance on layouts, including on-street, on-plot, garaging and parking courts, with examples of good and bad practice.

- Rear Parking Court with two access and trees

- On plot side parking

- On street parking

- Frontage Parking

- Covered parking Area

- Forecourt parking seen from street

Successful places:

• Provide a mix of parking options appropriate to site location and context.

• Integrate parking into the design/layout without detracting from the character or appearance of the place.

• Provide parking environments that are attractive, convenient and safe.

• Generate activity/movement between dwellings and the street creating safe, animated places.

• Provide surveillance of parking areas from adjoining buildings and gardens.

3.9 Street Design

3.9.1 Streets not roads

Roads should be safe, inclusive and an integrated component of the design in a way that helps create streets and places not just roads for carrying traffic

3.9.2 In order to achieve high quality, innovative and attractive residential places the Highway Authorities of Derbyshire and EMCCO are committed to working closely and flexibly with Local Planning Authorities, developers and other stakeholders in the process.

3.9.3 Whilst it clearly remains important to consider safety within the design, the overall philosophy has evolved from providing highways for the movement of vehicular traffic to the creation of streets and places that prioritise the movement of pedestrian and cyclists first, but which are also established seamlessly, in their own right, within the urban fabric.

3.9.4 It should be appreciated that a more flexible approach also places greater responsibility on the Design Team to demonstrate that the proposals will operate safely and satisfactorily, are maintainable and sustainable. Green technology introduces new street functions such as Solar lights and Electric charging points to be incorporated within the streetscape.

3.9.5 Full design guidance is contained within the Delivering Streets and Places 2017 (known as 6C's) document. It is not necessary or desirable to replicate substantial parts of that guide within this SPD and the information below therefore provides an indication of the main technical design issues to be considered and addressed. It is stressed that the content of Planning Streets and Places document should not be interpreted as promoting specific standards or as prescriptive. It is accepted that unnecessary rules and restrictions can inhibit innovation and, as a consequence, can prevent schemes from reflecting local character and distinctiveness. The guidance should therefore be used flexibly within the context of place in a holistic design process.

3.9.6 Junction & access visibility splays. It is expected that the design speed of streets within residential places will not normally exceed 20 mph and that speed restraint will be achieved through the design and layout of the streets and the locations of buildings and features, and not by using physical traffic- calming features.

3.9.7 Generally, for a 20 mph design speed, visibility should be available from a point 2.4m back from the carriageway edge of the priority route, representing the distance between the front of a vehicle and the driver's position. From this point visibility of 25m (27m for bus routes) should be provided measured along the nearside carriageway edge.

3.9.8 Where the visibility splay is at a street junction it will generally need to be constructed in a manner such that it is eligible for adoption as highway maintainable at public expense. At private accesses the splays must be capable of being kept free of solid structures or dense planting, and an appropriate condition of planning permission may reflect this.

3.9.9 The Highway Authority will consider changes to visibility provision, if it can be demonstrated that vehicle speeds will be restricted as a result of the design and layout of a scheme.

3.9.10 Intervisibility between driver and pedestrian should also be maintained at private accesses by the avoidance of solid structures and dense planting immediately adjacent to the access, at the rear of the footway. However, boundary treatments can be important elements of character and in defining street edges. A balance therefore needs to be achieved that maximises enclosure/definition, while satisfying any intervisibility requirements.

3.9.11 Carriageway widths. Generally, where there is separate footway provision adjacent to a carriageway, the carriageway should be minimum 4.8m wide for access to up to 50 dwellings and minimum 5.5m wide for up to 400 dwellings. Carriageway widening will be required on bus routes and where it is intended to accommodate on-street parking. However, within any scheme it is expected that carriageway widths should also reflect the role and function of the street within the overall street and place hierarchy, having regard to the context and the character of development being created.

3.9.12 A surface shared by all users, appropriate for up to around 50 dwellings, should normally be 8.8m wide. Additional widening may be required to accommodate any proposed on- street parking. Where sections of narrower shared surface carriageway are proposed these will need to be discussed with the Highway Authority. Corridors may reduce to 7.5m where there is development on one side of the road (comprising elements of service strip, carriageway and margin).

3.9.13 Care is required to avoid single-surface areas that appear out of scale with the domestic buildings flanking them. Changes of material or material unit size that are appropriate to the use of the space (defining vehicle routes, thresholds to drives/parking courts, entrances to buildings, defining key pedestrian crossing routes etc.) should be used, so that the landscape design responds appropriately to the scale of the space, to ensure it is proportionate and functions appropriately.

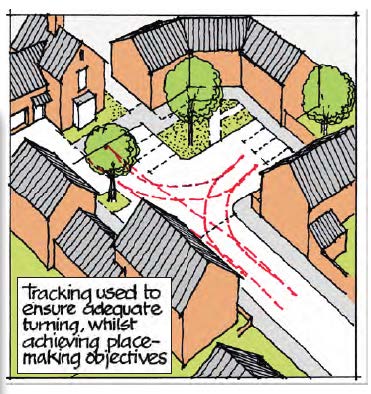

3.9.14 Vehicle tracking. Vehicle tracking assessments will be required as necessary, in order to demonstrate the traffic can be satisfactorily accommodated without, for example, having to mount kerbs and footways. This should take account of any planned or likely on- street parking.

3.9.15 Footway widths. Footways should be minimum 2.0m wide but subject to widening as necessary to reflect function within a particular place or context. In some circumstances it may be possible to provide a full width footway on only one side of the street, for example where the street would serve only a small number of dwellings or is a particularly narrow site. Conservation areas or rural settings may dictate a more informal approach to the design. Although it is likely that the footway would be necessary on both sides of the junction radii to aid pedestrian crossing.

3.9.16 Junction radii. Radii should not normally be greater than 6m in order to restrict vehicle entry and exit speeds and to avoid excessive crossing distances for pedestrians. Reduced radii may also be accepted subject to consideration of the design context and to the submission of tracking diagrams that demonstrate the route of vehicles relative to the proposed layout.

3.9.17 Changes in pedestrian priority encourages the reduction in radii to allow for continuous pedestrian flow rather than for prioritising the car. Smaller radii of 2 – 4m will be encouraged in housing layouts.

Good connectivity is key to reducing reliance on cars, especially for short trips. A good quality movement network will improve health and wellbeing and by providing well designed pedestrian and cycling routes throughout.

Derbyshire County Council Planning Streets and Places, September 2024 provides examples of street layouts that are acceptable to the county and gives sections showing a hierarchy of streets and acceptable dimensions.

The hierarchy is given below:

- Enhanced street

- Informal street

- Pedestrian prioritised street

- Private drives

- Industrial road

- Private streets

- Non-motorised vehicle category – cycle tracks (see LTN 1/20)

Occasionally the County Council will ask for different paving. Early discussion with the County Council is required to ensure that proposals will be accepted and adoptable.

Preference will be for an in verge or dedicated tree pit within the pavement and also within build outs between parking spaces. Occasionally the frontage verge may still be within private ownership. Where this occurs a management company approach may be acceptable.

Tree spacing should be coordinated early on in designs so there is no conflict with crossing points and bus stops, utilities and lamp posts and signage, whilst fulfilling urban design considerations. Spacing depends upon species and needs to be considered early in the layout process.

Enhanced Streets

The purpose of enhanced streets is to allow for multiple modes of transport with attractive main routes.

Street trees are planted within a verge or within dedicated grilles within allocated parking areas. The trees will be trees suitable for avenue planting and achieve a height of 12-20m at maturity.

Informal Street

Formal traffic controls are absent or reduced. Less differentiation between footway and carriageway. 5.5m to 6.2m (if Bus Route). Footpath 2m each side. Cycleways on street. On street visitors parking 1.8m wide on either side. Optional 2m Verge. Street trees required in all circumstances. Use of Tarmac, block or contrasting colours at focal points.

Pedestrian Priority Street

Pedestrian Priority streets are the default design standard for all new residential developments. 15mph design speed. 4.1 m to 6.2m (if a bus route). Footway min 2m wide. Cycleway on street. Informal on-street parking at widened points. Combination tarmac and block paving.

Private Driveways and Courtyard parking

• A private driveway can serve one or more properties, up to a maximum of 10.

• Minimum of 4.1m for first 15m.

• No pavements and all off street parking.

• Refuse collections within 25m of highway.

• Private drives should not block access to Public Open Space.

Public Rights of Way

Designs should encourage walking by providing connections to, and creating, new footpath only rights of way. These should be characterful and link to areas of landscape and countryside, using green corridors. Early discussion with the County Council's Public Rights of Way (PROW) Officer is required to protect and establish the legal rights of new footpaths.

3.10 Street Trees

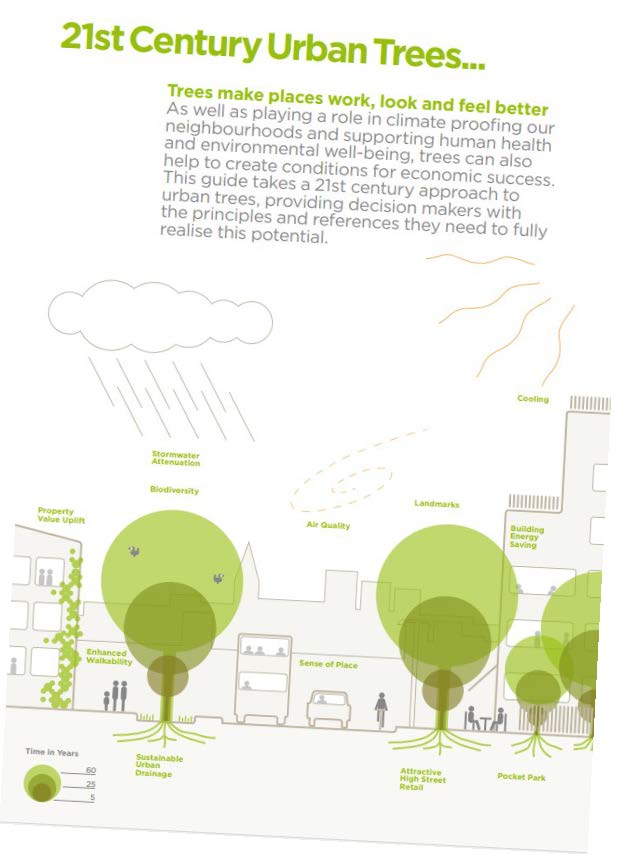

3.10.1 The NPPF requires that new streets are tree lined unless there are clear, justifiable and compelling reasons why this would be inappropriate. This provides opportunities for enhanced green infrastructure and more innovative drainage solutions. Tree-lined streets improve the aesthetics of places and create beautiful and sustainable places The retention of existing trees and location the right trees in the right places can significantly improve design quality.

3.10.2 Streets and roads make up around three-quarters of all public space – their design, appearance, and the way they function have a huge impact on the quality of people's lives as well as economic and social vitality and environmental sustainability.

3.10.3 Within large and medium residential schemes the Council expect to see a substantial amount of tree planting in tree-lined avenues, with good specimens that reach their full growing potential. Street trees should be located in ways that aid placemaking. Small trees scattered throughout a scheme will be discouraged.

3.10.4 Street trees should reflect the street hierarchy and be coordinated with utility services and street furniture within the overall design concept. They should also be used to reinforce the distinctiveness and local context of the place. Reference should be made to Local Landscape Character using predominantly local species within the planting framework for new development according to the character area type.

3.10.5 Incorporating new and existing trees at the early stages of project development plans is essential.

3.10.6 Create space to integrate trees into the design and implementation process. Provide dedicated verges and avoided using private garden spaces.

3.10.7 Where space is tight and in very limited circumstances the use of garden space within a management company plan for street trees would be considered acceptable.

Provide tree-lined streets because:

• People respond positively to a more beautiful aesthetically pleasing streetscene that provides a sense of place.

• Street Trees improve microclimate and reduced heat traps:

• Trees helps to filter pollution from the air and improve air quality.

• Trees and green space also contribute to the absorption of excessive water and are able to mitigate flooding events.

• Trees contribution towards a reduction of noise: A set of trees and plants wider effective noise barrier, reducing sound by 5-10 decibels.

• Trees work as wayfinders and townscape markers providing backdrops and framing buildings and acting as focal points along streets.

3.11 Public Realm Design

3.11.1 Creating robust, quality places

Areas of public realm should be both robust and attractive

3.11.2 High quality public realm adds significant value to all forms of development. In residential schemes, this value is reflected both economically in higher rents and property values and through enhanced quality of life, including through reductions in crime and anti- social behaviour.

3.11.3 Appropriate development of schemes following the place making principles set out within the SPD will create high quality public realm space; attention to the detailed design of these spaces will ensure their successful delivery. Public Realm needs to be integrated into surrounding street patterns.

3.11.4 There are two aspects to the detailed design of these spaces; hard landscape and planting. Poor execution of either of these design aspects can have a permanent negative effect on a scheme. Developers should consider commissioning landscape architects to undertake the design of these aspects on all but the smallest schemes.

3.11.5 To ensure that the public realm is appropriately considered and capable of delivery, full details of the hard landscape and planting designs is preferable at the submission stage of any planning application. Where full details are not able to be provided at this stage, visuals of proposed conceptual approach to the treatment of the public realm are strongly encouraged. Hard and soft landscape should not be designed as a separate element or an afterthought, but as an integral component of the overall design.

3.11.6 Hard Landscape

Using a simple palette of complementary materials, the architecture of an area and the activities of its inhabitants should give character to the streets

The choice of hard materials must reflect this intrinsic street character whilst also achieving continuity of movement, flow and, with it, connectivity

3.11.7 The design of the public realm should not exaggerate the diverse character of places.

3.11.8 The hard landscape comprises paving, steps, ramps, boundary features, and street furniture. A good design will bring these elements together in a coherent manner that is appropriate to the needs of the individual scheme, not an ad-hoc collection of 'standard details'. Use of low walls for example, within shared streets encourage sitting out and can be easily designed into frontage thresholds.

3.11.9 The most important function of paving is to provide a hard, dry, non-slip surface that is durable, easily maintainable and that will carry the traffic that needs to use it. Analysis of successful paving illustrates that there is rarely a change in material or surface pattern without a practical purpose. The choice of materials and design detailing must be capable of satisfying all of these functions and can be summarised into the following requirements:

• Be fit for purpose and hard wearing.

• Be simple and unifying.

• Be sustainable through lifetime costing / valuing.

• Be attractive and add to the placemaking qualities of a scheme.

Successful Healthy Places:

• Reinforce character. Paving brings unity to diverse places and nebulous areas that need a common background and immense variety is obtainable within a limited range of materials. Alien paving patterns or an excessive variety of materials often creates confusion.

• Provide a sense of direction. Examples include pedestrian routes across squares and parks, or, service vehicle routes through shared surface areas. Successful routes are direct.

• Provide a sense of repose. Neutral, non- directional paving has the effect of halting people. Areas of sitting, meeting, or gazing to distant views should be paved in this way.

• Indicate a hazard by change of material or pattern. For example, paved junctions at side streets warn drivers that they are crossing or entering a pedestrian environment. This technique must be used consistently across a scheme.

• Reduce scale. Introducing a change of material to affect the scale of a space requires subtlety to avoid making the paving overly important. Paving should not aggressively proclaim its presence but provide background.

• Provide inclusive mobility: It is important to use appropriate tactile paving to enable inclusive mobility. This includes different styles of paving to guide and warn and explain different types of crossings.

• Comprise the right material for the space. Rigid materials such as slabs and blocks work best in geometric forms where cutting can be minimised. Where the space is fluid, for example curved edges or undulating ground, flexible materials such as concrete, blacktop or small unit setts should be used.

• Create appropriate boundaries. Fences, railings, and walls must be selected according to their function. Ask if they are required at all? Would they be robust enough for their location? Are they the right height? Ensure there is continuity in types of boundaries and keep materials to a simple palette. Walls should not dominate the streetscene.

• Reduce clutter. Minimise street furniture to reduce clutter and long-term maintenance liabilities. Keep street lighting to the back of kerbs or on buildings and minimise the use and number of poles for signage. Use bollards to protect vulnerable areas, not to overcome the problems of a poorly designed layout – e.g. keeping cars off 'left over space'. Put seats where it would be comfortable and attractive to sit, include some benches with backs to assist the elderly.

• Reduce large areas of tarmac. Within modern housing estates, attempts to be contextual have been diluted by the overuse of tarmac. Hard surfaces should be reduced where possible and planting should be increased.

• Provide maintenance access. Anticipate where maintenance vehicles may need to go and ensure that the paving is capable of taking the weight – e.g. access to light columns, green areas for grass cutting, and play areas.

Above and right: Poorly considered public realm detracts from the quality of the environment.

Above: Good quality materials make an important contribution to the character of the place.

3.11.10 Planting

Planting should create and reinforce character, scale, continuity and variety throughout the seasons.

3.11.11 It is not the primary role of planting to soften visually harsh environments, screen off poor design or fill left over space.

3.11.12 Planting can promote biodiversity, help combat aspects of climate change by absorbing CO2, offers shade and reduces reflected heat from hard surfaces aiding cooling and reducing energy use.

3.11.13 Planting is made up of trees, shrubs, grass and aquatics. They all need space to grow, both above and below ground. They also require appropriate drainage, water, nutrients, and maintenance to thrive.

3.11.14 Planting schemes should be developed as part of the overall design public realm with emphasis on the 3rd and 4th dimensions, not just in plan form.

3.11.15 Consider the eventual size of the planting, ensuring that there is both space for it to grow, and that its impact will not be detrimental to adjacent constructions or uses. Remember that plants are living things and that interesting layouts on plan will not be realised if their environment is hostile.

Successful places:

• Reinforce character. Planting should provide enhancement, focus, and intimacy, positively contributing to the quality of space. Planting is an integral part of the overall design and must not be used simply as a space filler or barrier.

• Deliver quality rather than quantity. The creation of green oases and strategically located planting must have real impact, in terms of scale, location, and nature.

• Consider location. Planting may be inappropriate in locations where it would obscure important features and facades or traffic sight line requirements. Position planting where it will survive its environment and flourish, coordinate with underground services to promote successful growth.

• Have realistic expectations. Whilst it is best to plant street trees directly into the ground, they should be given sufficient space to avoid their roots being cramped by buildings, street foundations, or constrained by underground cables and pipes. They face damage from vehicles and contend with air and soil pollution. Pavements also restrict air and water from reaching the roots. Use a suitable tree pit and growing medium to maximise their chance of survival.

• Use Gardens. Residential Gardens can contribute to nature. Nature based planting schemes using native plants are encouraged. Use hedgerows to front gardens to reinforce biodiversity in a scheme.

Key Issues:

Developments have a duty to deliver a mandatory minimum of 10% Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG). The requirement applies to large and small sites. Small sites are generally defined as residential developments with 1-9 dwellings on a site of 1 hectare or less.

The Council's Advice Note: Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) April 2024, explains about preserving biodiversity by creating or enhancing habitats through new developments and sets out the requirements.

The landscape character is the key defining context of the landscape design. This will help to provide a framework for the development with natural assets establishing the character of the structural planting for the development. We need to view landscape in its natural character type rather than an 'anywhere landscape' where trees and plants are generically used.

Landscape should be seen as the setting for the houses being laid out. There needs to be an emphasis on native planting, reinforcing landscape character and adding links to the surrounding landscape context to create nature recovery.

Awareness of space requirements from utilities and cable runs need to be determined early on in the design process and measured against space for planting.

All landscape schemes should demonstrate increases in biodiversity, aesthetic values and recreation.

Biodiversity Design Guidance:

• Be holistic. It is important to provide a structural planting framework to the planting design rather than a mélange of plants depending on availability. Early planning can ensure availability of a strong plant palette.

• Be sustainable. The detailing of tree pits is fundamental to success and should be as large as possible. It is preferable to plant trees in uncontained, free draining tree pits and to sustain growth, it is essential to back-fill with good quality, nutritious urban tree soil. Ideally, plant trees in groups, with the tree pit forming a continuous trench or island of soil.

• Integrate with hard areas. Tree grilles maintain the continuity of paving around trees, protect and aerate tree root systems and allow rainwater irrigation. Tree grilles are also an important visual element.

• Borrow landscape. Planting in private gardens will have a positive impact on the public realm too. Planting trees in front gardens is encouraged but not as substitute for meaningful street tree planting. A significant drawback to planting in private space is the loss of long-term control over the overall scheme – freeholders may choose to remove any planting on their property.

• Safety and security. Planting design should take full account of minimising opportunities for crime and anti-social behaviour when selecting locations and species for planting. Planting should support secure by design principles by providing buffer zones between public and private spaces, avoid creating areas for concealment and not unreasonably impeding natural surveillance.