Bolsover Successful Healthy Places SPD 2025

2. Delivering Quality: The Design Process

2.1 Good Design and Healthy Placemaking

2.1.1 Everything that is made is the product of having been through a process of design and the built environment is no exception. However, good design does not just happen by itself, it is the result of a creative process and involves not only good designers but a commitment from key decision makers to achieving it.

2.1.2 Good design also includes placemaking. Placemaking is the process of involving communities in establishing what good design means to them through consultation and engagement. Placemaking can empower communities to have a sense of belonging and pride in their local area as places change over time. (Home England Fact Sheet 6 Nov 2022).

2.1.3 Ultimately, it is about creating buildings and places that are well built, will work well and that look good. Working on these principles of good design will help deliver successful places and balancing these objectives does not need to add expense to the project (Cabe, Evaluating Housing Proposals Step by Step, 2008). Achieving good design should be the aim of all those involved in delivering residential development.

2.1.4 The Design Council's Healthy Placemaking Report 2018. explains that it is also about delivering places that are sustainable and support health and activity.

2.1.5 High quality places transcend subjective issues of personal taste, style or architectural fashion, with three fundamental principles at the core of design excellence.

2.1.6 Well Designed: Places that are visually pleasing or even delightful. Inspiring pride of place. Essentially places that look good.

2.1.7 Enduring: Places that are useful and that are fit for purpose, fit to last and easy to use, contributing to a balanced and good quality of life. Essentially places that work for everyone and are easy to maintain.

2.1.8 Successful: Places that stand the test of time, that support community and foster healthy lifestyles.

2.1.9 The National Design Guide 2021 breaks these down into ten characteristics:

Context – enhances the surroundings.

These 10 individual characteristics work together to contribute to the character of a place. In turn, these ten characteristics help to nurture and sustain a sense of Community. They work to positively address environmental issues affecting climate. They all contribute towards the cross-cutting themes for good design set out in the National Planning Policy Framework

Part 2 of the National Design Guide outlines the characteristics in detail. The assessment of planning applications has regard to these 10 characteristics.

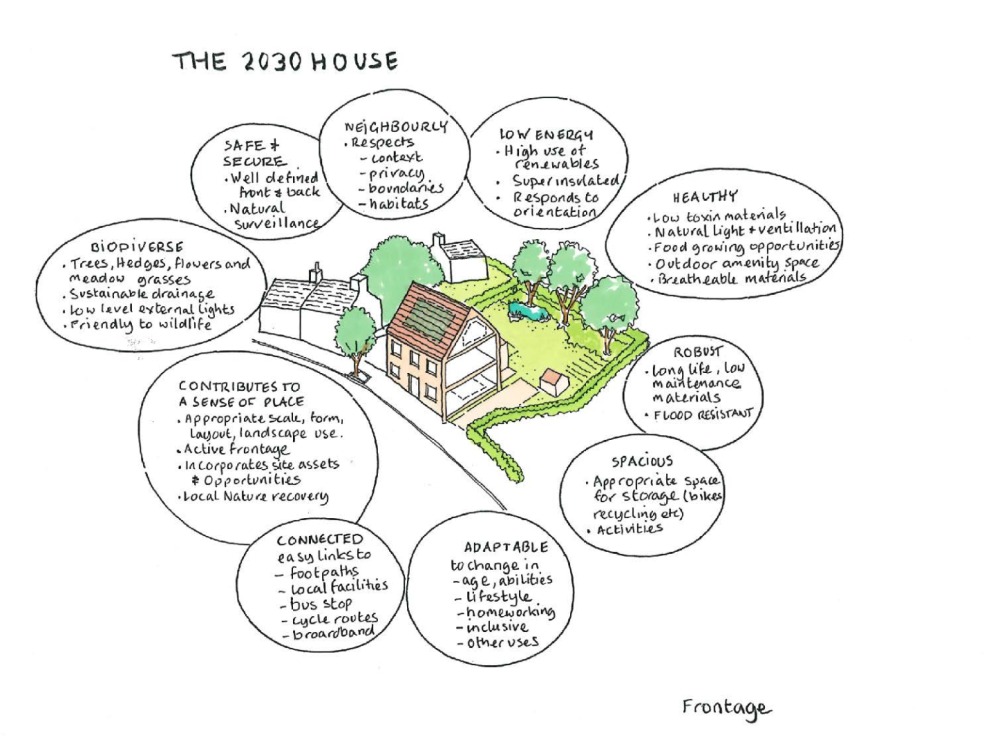

2.2 Home of 2030

2.2.1 In response to the United Nations 2030 Sustainability Agenda, The Design Council have set about creating a vision for the Home of 2030. Through wide ranging public consultation they have identified the following key conceptual changes:

• Making new homes desirable to all demographics is key to the Home of 2030. Homes can adapt to changing needs and work for an ageing society, allowing people to live at home longer.

• A key factor was that people wanted more robust design quality so that they did not need to spend time fixing things. This is an issue regarding longevity of materials, renewable of materials and recycling.

• People want their homes to reflect the diversity of their experiences and needs.

• Drive innovation in the provision of affordable, efficient and healthy green homes for all.

2.2.2 In essence, the expectation is that future homes are to be visually pleasing, as well as being functional and with a respect for the context and place they are set in. They can be innovative and locally distinctive using sustainable materials and technics to enhance standards for future living.

Principles for the Home of 2030:

• Being fit for purpose

• Giving people agency

• Addressing the climate crisis

• Connecting people and their communities

• Meeting the needs of every life stage

• Representing something different

What Does the home of 2030 look like?

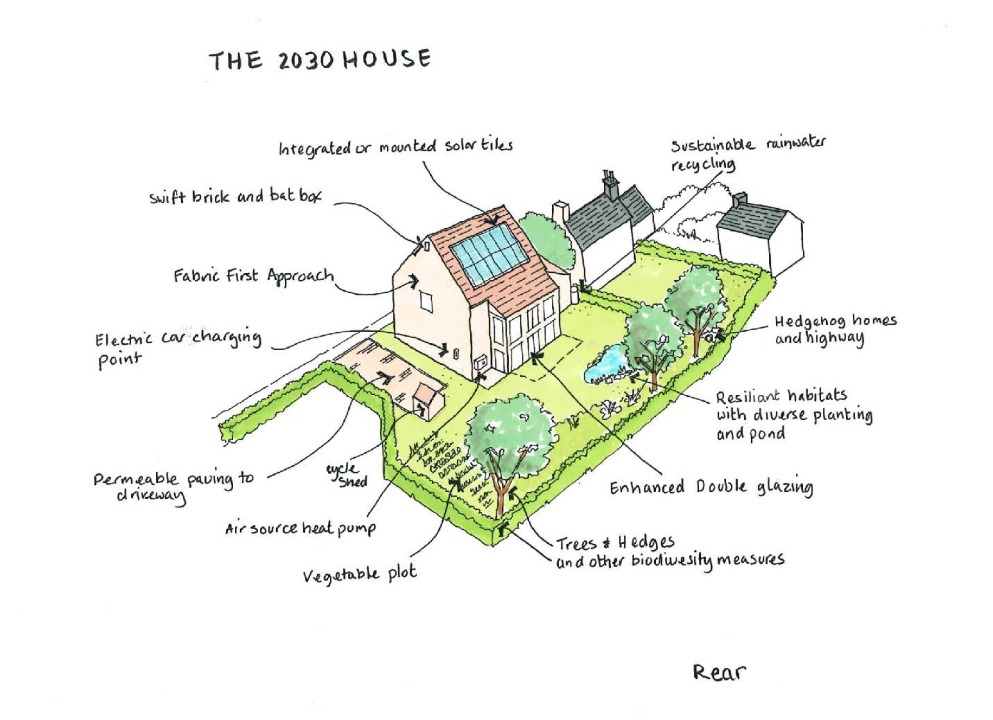

2.2.3 The Home of 2030 in Bolsover will accommodate innovation to address the climate crisis with the use of new types of materials to be encouraged within new housing schemes. Where design solutions are required to specifically fit the social, economic, and environmental context of a particular community or location, these will be sensitive to the placemaking qualities of the area. Driving innovation will also mean considering retrofitting existing houses and the changing appearance of new houses.

2.2.4 The home of 2030 in Bolsover will be built with the potential to include more features to address climate change challenges. The use of new types of materials and creative ideas are to be encouraged in new housing projects. In situations where solutions need to be tailored to a specific location, they will be designed to consider the special qualities of the place.

New homes are now expected to enhance opportunities for environmental improvements that improve local drainage, increase habitat creation and provide more green space for climate mitigation by incorporating sustainable drainage, low level lighting, and native planting schemes.

Planning for net zero homes

2.2.5 Dealing with the climate emergency has resulted in the drive towards ending the use of fossil fuels. The Future Homes Standard (FHS) is set to be introduced in England from 2025, alongside the Future Buildings Standard for non-domestic buildings. The standard will be in line with upcoming regulations covering Part L (conservation of fuel and power), Part F (ventilation) and Part O (overheating). Its primary aim is to significantly enhance the energy efficiency of new homes and reduce carbon emissions.

LETI's Climate Emergency Retrofit Guide shows how to retrofit existing homes to make them fit for the future and support the UK's Net Zero targets. It defines energy use targets for existing homes and provide practical guidance on how to achieve them.

LETI's Climate Emergency Design Guide aimed at new buildings covers 5 key areas in the design and operation of buildings, particularly in the context of climate change and the drive towards net-zero carbon emissions: operational energy, embodied carbon, the future of heat, demand response and data disclosure. The methodology includes setting the requirements of four key building archetypes including the small and medium house.

BREAAM certification assesses the whole life performance and sustainability of new housing projects.

It applies to a wide range of building types, including commercial offices, retail, industrial, education, healthcare, and residential. BREEAM assesses a building's environmental performance across various categories, such as energy, water, waste, health and wellbeing, pollution, transport, land use, ecology, and management. BREAAM certification is supported by the Council.

BRE's Home Quality Mark, (HQM) is a specific scheme tailored for new build residential developments, focusing on the quality and sustainability of homes. With Home Quality Mark (HQM) certification, developers and investors can show that their homes are sustainable and high- quality.

It's exclusively for new build homes, providing a benchmark for their design, construction, and performance. HQM assesses homes based on factors like running costs, environmental footprint, and the quality of living and amenity spaces.

As of April 16, 2025, HQM has been integrated into BREEAM and is now known as "BREEAM UK New Construction: Residential". This means that the assessment criteria and certification process for new build homes will now be part of the broader BREEAM framework.

Passivhaus is an international tool, a range of proven approaches to deliver new and existing buildings optimised for net zero. This effectively eliminates the 'performance gap', delivering excellent performance in-use. The 'performance gap' is the difference between the assumed energy performance of a building based on its design and the energy performance a building actually achieves. Passivhaus prioritises efficiency, of both energy and material resources.

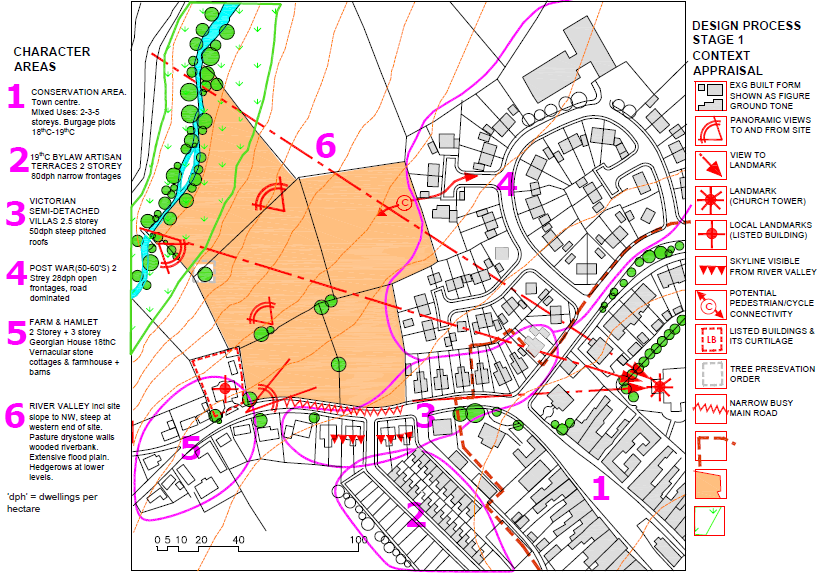

2.3 Context Appraisal (Step 1)

2.3.1 To achieve development that is appropriate to its context first requires an examination and understanding of the wider area beyond the site boundary, as well as the site itself, by undertaking a context appraisal and site appraisal.

2.3.2 The appreciation of context, including historic context (where applicable) resulting from these appraisals should generate creative design ideas for the site, identify positive opportunities to help 'ground' the development to the place, as well as highlight constraints or issues for resolution at an early stage in the design process. Where available, local studies such as conservation character appraisals and landscape character assessments can be useful references to help inform this approach.

2.3.3 A summary of the key findings of the appraisals and evaluation should be evident in the Design and Access Statement. However, an appraisal is more than a simple description or photographic record of the surrounding area, it requires an evaluation and explanation of how they have informed and influenced the scheme. This is a critical stage that should not be overlooked.

2.3.4 A landscape appraisal should evaluate the intrinsic character and beauty of the natural landscape. Natural capital and ecosystems are essential to good design and should form the basis of contextuality of the proposed approach. Any new development should have regards to the character of the surrounding natural landscape and the intrinsic quality of its setting.

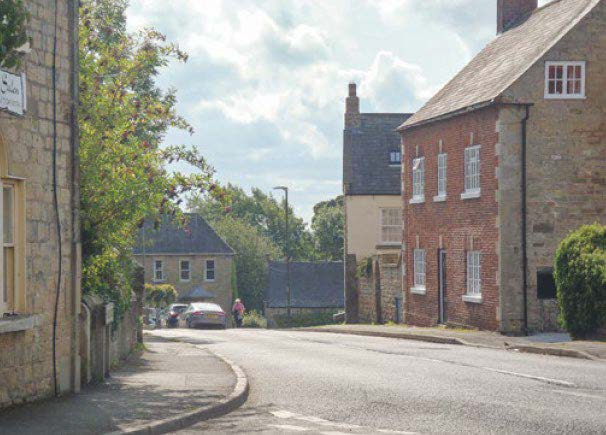

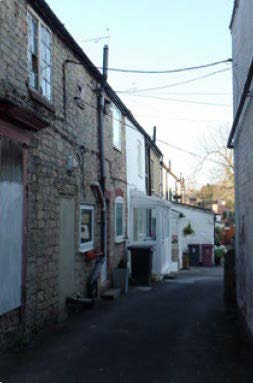

2.4 Bolsover Contextual Residential Character Images

2.4.1 Bolsover has a series of character appraisals for individual conservation areas that provide references to traditional building architecture and settlement forms found in the district. These are useful documents to provide visual clues and references to the style and patterns of development within the district. These appraisals can be found on the Council's website or by contacting the planning department.

2.5 Modern residential developments in Bolsover District

Contemporary Housing Styles in Bolsover

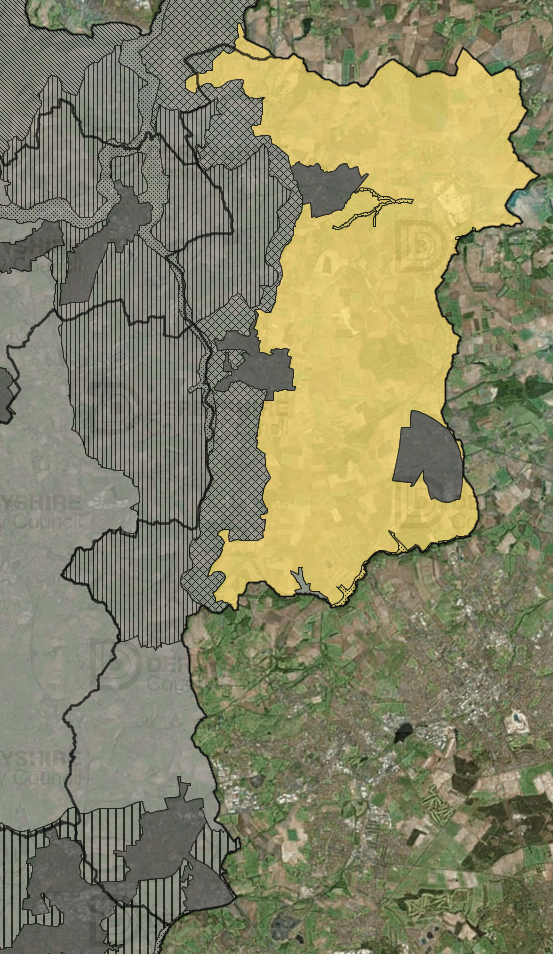

2.6 Landscape Character

Southern Magnesium Limestone

S. Yorkshire, Notts & Derbyshire Coalfield

Landscape Character:

Bolsover's rural landscape combines with the built form to create the districts unique character. Bolsover's two landscape character areas: S.Yorkshire, Notts and Derbyshire Coalfields and Southern Magnesium Limestone provide contrasting identities. They both contain a set of distinguishable characteristics that give the landscape it's identity.

The landscape is defined beyond nature and appearance. It is important to explore the history of the landscape, and how it has developed to serve the area.

The topography and natural features of each landscape character area has influenced the form of settlements and the buildings within them. Landscape character also contributes to the framing of key views within the district and as well as comprising important habitats for flora and fauna to thrive.

Landscape Character Areas:

This design guide should be read in conjunction with the Landscape Character of Derbyshire, 4th edition, 2014. This maps out landscape character types which share common characteristics. These are further subdivided into sub landscape types. Applicants should refer to the these when designing for further guidance. The map can also be accessed on the Derbyshire Mapping Portal.

Preservation of Landscape Character:

To maintain the distinctiveness of settlement form and the preservation of landscape character across the borough requires an understanding of the relationship between buildings and landscape, and the contribution buildings and human activity has on the character of that landscape.

Relationship of Landscape and settlements:

Landscape character should be considered in conjunction with settlement characteristics gathered from site visits, mapping and appraisals. The contribution of settlements or buildings to landscape character by virtue of their topographical position is of importance when considering extensions to existing settlements.

For example, a linear settlement may be located along a valley and be hidden by nature of its form. Alternatively, the same linear settlement located at the top of a hill, or along valley contours creates a potential landmark within the landscape. Similarly, the sense of arrivaland relationship within the wider landscape is very different between the two locations topographically.

Once the form of the settlement and the settlement typology is understood, consideration of the topographical setting should be considered. Consideration should be given to the effect of a variety of topographical factors such as elevation, slope and aspect on the design of a development on the form of the settlement.

Understanding variations in landscape form includes identifying differences in micro-climatic conditions. Different landscape forms may present different opportunities to respond to the climate emergency by orientating for maximum solar gain as well as structuring development to create the most walkable layout.

Each section of the Landscape Character of Derbyshire (2014) provides a list of native species relevant to the landscape typology, and a % mix in the landscape, either as occasional field trees, or hedgerows. This should be the starting point for any landscape setting of new housing schemes at the edge of settlements.

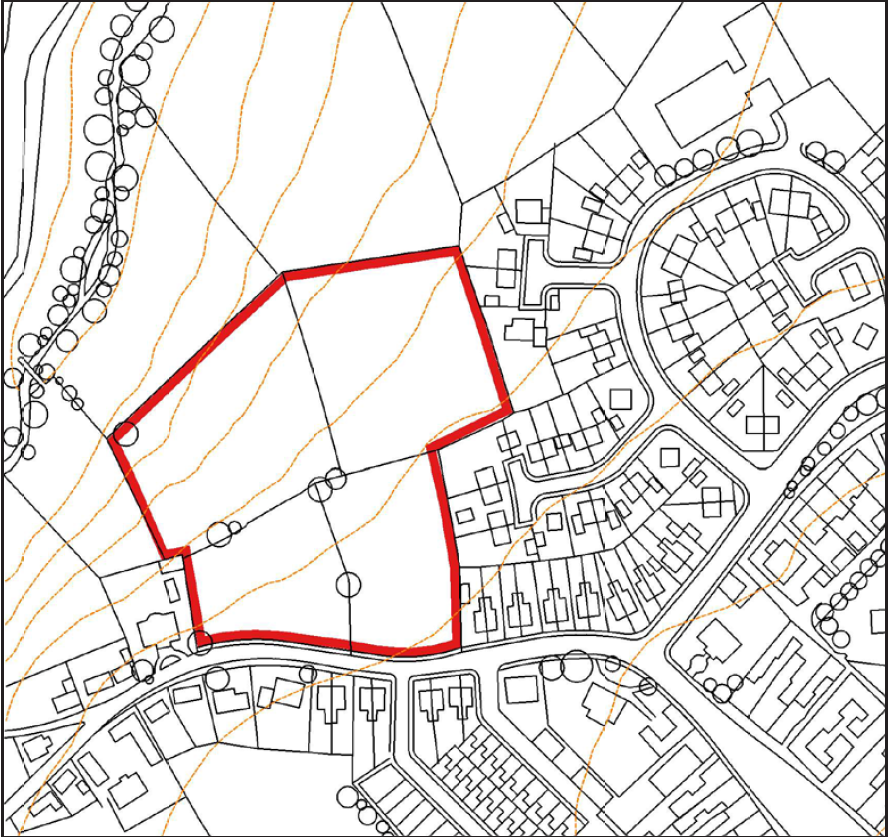

2.7 Understanding the Place (Step 1) Site Plan and Contextual analysis

2.7.1 Developers need to demonstrate they have followed a rational design process. The NPPF (Dec 2024) seeks to reinforce local distinctiveness (Section 12, Paragraph 135). This means understanding the surrounding area, and how it functions. Inward looking proposals are less likely to make a positive contribution to the character of the area.

2.7.2 Undertaking a context and site appraisal involves considering the value and quality of the site, component elements and its surroundings, including areas of particular character, views, buildings, landscape and other features and how they contribute to the character of the place.

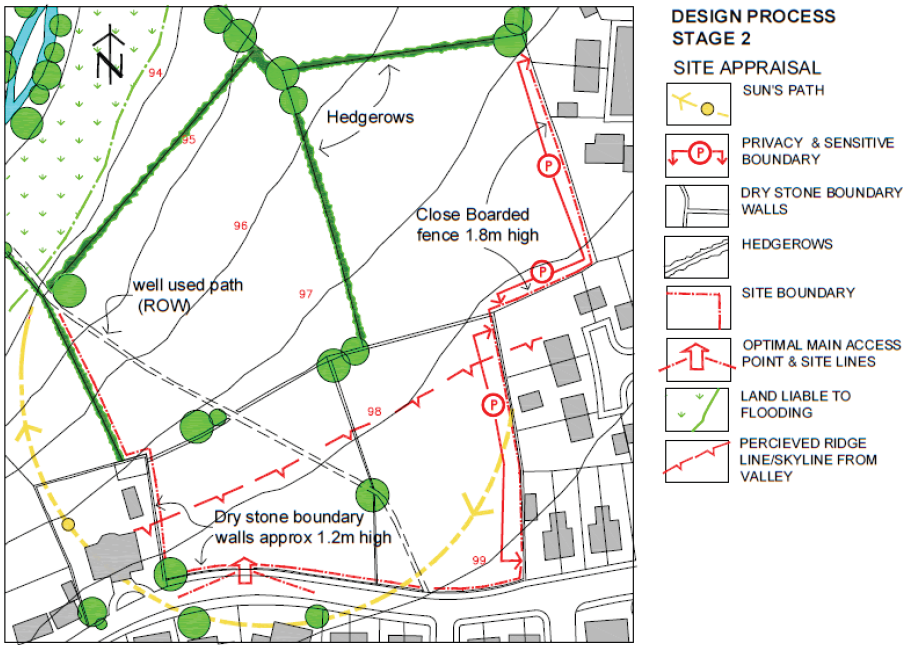

Site Appraisal and Concept (Steps 2&3)

The site appraisal should look in detail at the existing conditions. These include physical linkages to the wider area, entrances and desire lines, topography and levels, including the siting of existing buildings and landscape features. Site features such as watercourses, woodlands and hedgerows provide a natural framework. Boundary treatments and edge conditions inform relationships to adjoining sites.

Ground conditions, instability flooding and drainage issues require investigation. Orientation and microclimate should inform the siting of buildings. Heritage Assets and archaeology require specialist assessment.

Views into and out of the development, sensitive edges, and amenity issues. Any cultural references or local attachments should be noted.

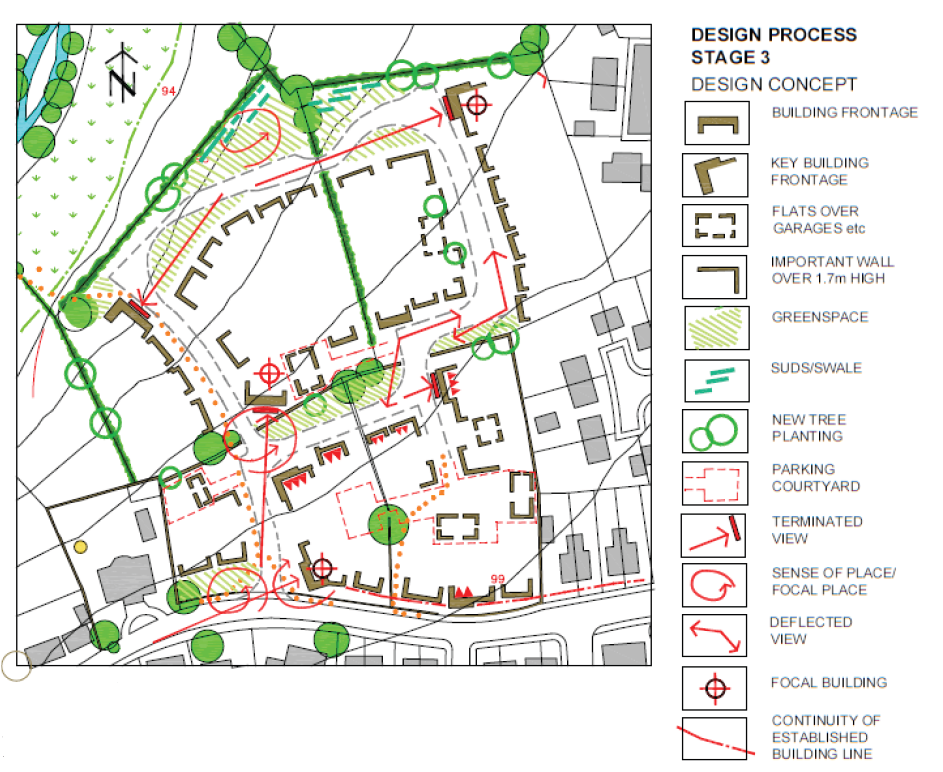

The development concept establishes the design and sustainability principles: key buildings and frontages, focal points, views in and out, main routes and connections. A range of options with alternatives to allow the resolution of conflicting issues.

Such conflicts should be explained and justified in the Design and Access Statement. It is at this stage that it is appropriate to approach the Development Management Team to discuss the design approach, prior to the development of detailed layouts. Depending on the sensitivity of the scheme, community consultation may be advised at this stage before progressing to detailed design.

2.8 Benchmark and Review Process and Design Codes

2.8.1 In order to maximise the benefit of pre-application discussions, as part of the initial approach the developer will be expected to provide the following information:

A site appraisal plan:

Identifying the location of the site within its wider setting, identifying existing areas of character, showing how it connects with and relates to adjoining parts of the settlement, character, local centres, transport, services, views, local geography etc. [Understanding the Place 2.7]

A site analysis plan:

Showing an understanding of the site characteristics particularly constraints and assets [Site Appraisal and Concept 2.8] from this,

A concept sketch/diagram:

To illustrate the abstract idea and communicate the key design principles by which the site is proposed to be developed [see also 2.8]

(NOTE: this is not a detailed design layout at this stage)

Please Note that the Council has have an application Validation checklist with design requirements. A Masterplan and Design Statement should be provided for all sites of 5ha or more or 150 dwellings or more. The Design Statement should assess the development against the criteria in the National Design Guide.

2.8.2 The design quality of proposals for residential development will be assessed using a number of methods. These may vary according to the nature of a particular development. However, the review processes will provide the benchmarks against which a scheme will be judged on design grounds. They will include:

2.8.3 Design Consultation: Where the service is available, the Urban Design Officer or equivalent, will be consulted on proposals for residential development and will provide a design consultation response. This will provide an opinion on the acceptability of the design aspects of the scheme. This may also be accompanied by, or in the form of a Building for a Healthy Life 2020 appraisal (see 2.9.9 below).

2.8.4 Regional Design Panel: Some schemes may be requested to be referred to the Design: Midlands, and independent Review Panel. Typically these may include large scale developments, or those of a strategic or particularly sensitive nature, although any scheme could potentially be referred if this is considered to be appropriate.

2.8.5 Applicants whose schemes are referred will normally be requested to attend a design meeting and to present their proposals to the review panel. The panel's comments will be used to inform the progression and refinement of the scheme.

2.8.6 Schemes may be referred to Design: Midlands at the pre-application stage and in many cases this will preferably be before the design of a proposal becomes too advanced or fixed. There is normally a charge for this service.

2.8.7 Local Review: The Senior Urban Design Officer will recommend referring selected proposals for residential development to an internal review group comprising a group of officers from the authority and consultees where required such as Highways, Leisure, Historic Environments, Police and Derbyshire Wildlife Trust.

2.8.8 Design Code: Where a Design Code exists for a site or where an applicant is requested to prepare a Design Code, this can form part of the Design and Access Statement or Design Guide accompanying the application.

2.8.9 Building for a Healthy Life 2020: When using BHL it is important that developers discuss with the planning department the 12 considerations at the very start of the design process, agreeing what is required to meet each consideration. (See pages 24 and 25.)

2.8.10 A Design and Access Statement (DAS) should be used to assist in the process. Design and Access statements are important to understanding key design decisions. It could be structured according to the BHL considerations. For large developments the design should also address the 10 placemaking considerations of the National Design Guide.

Building for a Healthy Life 2020

BHL is a national standard for well-designed homes and neighbourhoods and is about creating good places to live. Proposals for residential development are expected to demonstrate they have met these considerations. Proposals will be assessed against 12 considerations under three headings:

• Integrated Neighbourhoods

• Distinctive Places

• Streets for All

The 12 considerations reflect a vision for what new housing developments should be; attractive, functional, sustainable places, as summarised below.

Integrated Neighbourhoods

Natural Connections

Understand the wider context and 'stitch' a new development into a place.

Walking, cycling and public transport

Improve connection with local pedestrian and cycle networks within the site and a 3m radius with routes through green spaces, including prioritised and projected routes. Ensure access to all. Links to public transport networks.

Facilities and Services

Locate community facilities in the best location for those walking, cycling and using public transport.

Homes for Everyone

Provide a mix of housing types and tenures including first time buyer homes, family homes, homes for those downsizing and supported living. Maximise the opportunity offered for supported accommodate. Offer people access to private outdoor space for health and wellbeing.

Distinctive Places

Making the Most of What's there

Agree opportunities and constraints and explore how best to integrate existing assets such as hedgerows on and beyond the site. Use contours, water flows, natural lighting, cooling and ventilation. Draw all together in an Urban Design Framework (UDF) master plan, based ideally upon perimeter blocks to create continuous street frontages and public spaces that contribute to a sense of enclosure and safety.

A Memorable Character

Create a place with a locally inspired or otherwise distinctive character. Review the wider area for sources of inspiration. Delve deeper into architectural style and detail. Find inspiration in local history and culture and the essence of the distinctive character of settlements.

Well Defined Streets and Spaces

Ensure principal facades and front doors face the street and public spaces. Use perimeter blocks with clearly defined fronts and backs and carefully considered street corners. Active frontages, doors, balconies, terraces, front gardens and bay windows to enliven and create interest. Use 3D models to understand spatial qualities.

Easy to find your way around

Use legible features to help people find their way around a place. Street types, buildings, spaces, non-residential uses, landscape and water to help create a 'mental map.'

Streets for All

Healthy Streets

Consider streets as part of the public realm. Create boulevards and streets with trees and active edges. Incorporate low speed streets and neighbourhoods with pedestrian and cycle priority. Create a balance between movement and place functions. Healthy Streets improve physical and mental health, encouraging walking, cycling, outdoor play and safety for young children and social interaction. Introduce priority for pedestrians and cyclists across junctions and accesses.

Cycle and Car Parking

Well design developments will make it more attractive for people to choose to walk or cycle for short trips. Provide secure cycle storage close to people's front doors. Integrate car parking into the street environment. Anticipate realistic parking demand. Differentiate Car ownership and car usage. Create solutions for attractive, convenient and safe cycle parking.

Green and Blue Infrastructure

Creative surface water management such as rills, brooks and ponds enrich the public realm and help improve the sense of wellbeing and offer an interaction with nature. Introduce lost habitats and weave habitat creation throughout development. Plan movement corridors. Create food growing opportunities such as allotments and orchards on larger developments. Have a sustainable drainage system. Use a treatment train, use rail gardens, ponds, and swales.

Back of pavement, front of house

Use of hedges to define public and private spaces. Front space has a significant impact on the quality of place encouraging people to personalise their homes. Integrate services, waste storage and utilities cabinets. Outdoor amenity space for apartment buildings such as balconies for relaxing or drying clothes.

2.8.11 Building for a Healthy Life is not an end in itself, but a tool for assessing how well schemes for residential development meet the requirements of local design policies. It forms a framework for design discussions between the stakeholders and provides a measure of the design performance of a scheme which can be used to assist in the decision-making process.

2.8.12 Where possible, the Design and Access Statement (DAS) should be used to assist in this process e.g. it could be structured according to the BHL12 questions (provided all the requirements of a DAS are addressed). Guidance on how to write, read and use DAS can be found on the Government website. The Design Council have also produced guidance, Design and Access Statements: how to write, read and use them (2006).